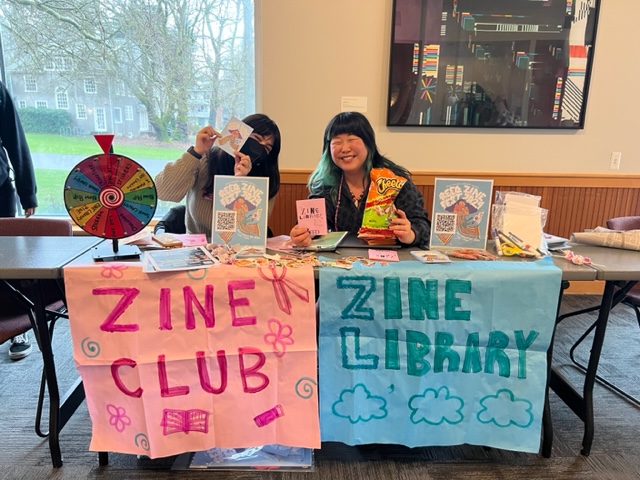

Check out the zine and arts programs that lead up to the final event in 2024, the Reed Zine Fest!

Read about the librarians behind the series of zine and art programs!

ANNOUNCEMENTS

📌 Masks are required for Reed Zine Fest. We are offering KN95 masks and a limited number of tests to attendees at the Zine Fest welcome desk.

👉 Follow @reedzinelibrary for updates!

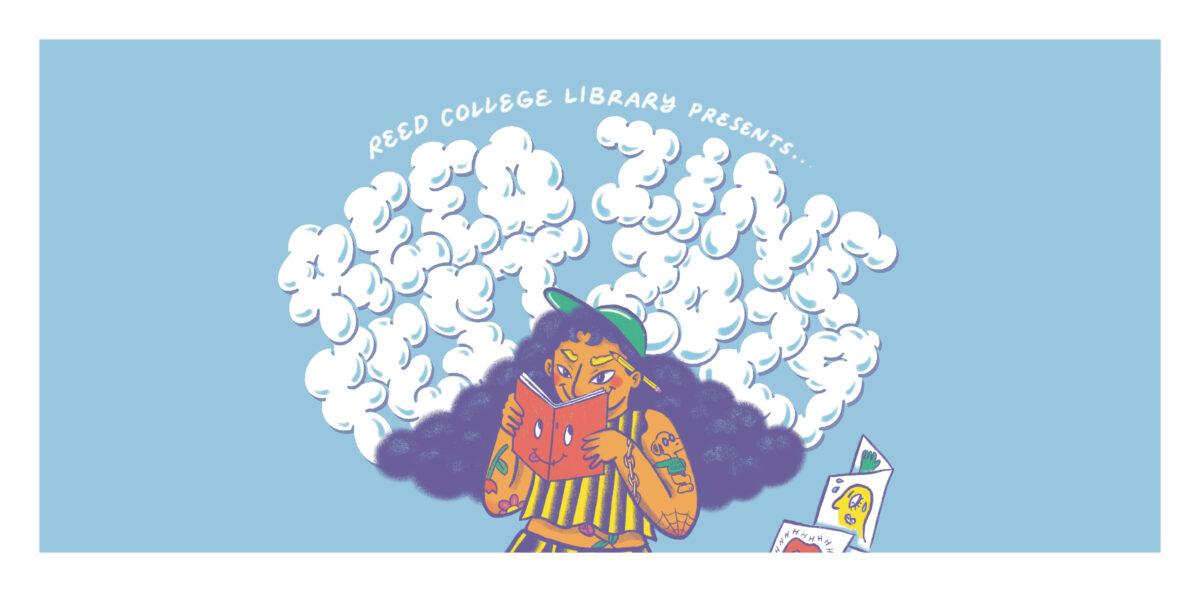

🎨 Reed Zine Fest artwork by Portland-based artist Jax Ko.

📌 Parking: Parking is free! We suggest that you park in the West Parking lot off SE 28th Ave (parking is free). If that lot is full, you can park in the East Parking lot and the North Parking lot. Please do not leave any valuables in plain sight. Reed College is also off the Bus lines #10, 19, and 75.

👉 Parking to Kaul Auditorium (map):

- West Lot – If you park here you can walk around the Performing Arts Building (PAB) on the path or go through the building and take the elevator. Either option will lead you to Kaul Auditorium which will be on your left.

- North Lot – If you park here note that you will need to cross the Canyon Bridge to get to the South Side of campus and then follow a path to Kaul.

- East Lot – If you park here please note that it will be a 5 to 10 minute walk across campus. While there are paths, and signage, the path is not smooth and there are slight inclines.

ZINE FEST

✂️ Reed Zine Fest with keynote James Spooner

Saturday, March 30, 11 a.m.- 4 p.m. at Kaul Auditorium

Reed Zine Fest is the first zine fest organized by the Reed College Library to celebrate independent publishing, DIY, and zine making. This one-day festival will feature both local community and Reedie zinesters, workshops, and a keynote by special guest James Spooner (Black Punk Now, graphic novel The High Desert, Director of the Afro-Punk Documentary and the co-founder of the Afro-Punk Festival).

Zine Fest Schedule

| Time | Happening | Location |

| 11AM | Reed Zine Fest opens! | Kaul Auditorium |

| 12PM | Keynote with special guest James Spooner | PAB 320 |

| 1:15PM | Remembrance table for Tonya Jones, Leader of the WOC Zine Collective, collecting donations for Tonya Jones’s son | Kaul Auditorium |

| 2PM | Goodbye Cruel World and Dear John: How to Write a Letter You’ll Never Send with Olivia Olivia | PARC |

| 3PM | Beyond Staples: Alternative Binding Methods with Erin Moore | PAB 332 |

| 7PM-11PM | ZINE AFTER PARTY!!! HORSEBAG, ZEROCOOL, & MIJA!!!!!! | Reed Library Lobby |

MRC Student Lunch with James Spooner (MRC students only)

Saturday, March 30, from 1 p.m. – 2 p.m. at the MRC

Join us for lunch at the Multicultural Resource Center (MRC) featuring James Spooner, the award-winning author of the coming-of-age graphic novel memoir, “The High Desert.” Don’t miss this unique opportunity to interact with a notable author and engage in meaningful dialogue about his work! Special thanks to Lily De La Fuente the Humanities Librarian for leading and selecting The High Desert for the Fall 2023 MRC Book Club. Due to the exclusive nature of this event, registration is required, and attendance is limited to 25 students.

Support

This series of zine and arts programs is generously funded by the President’s Office, the Office of the Dean of Faculty, the Office of Institutional Diversity, the Cooley Gallery, the Office of Student Engagement, the Student Life Office, and the Library.

Past Zine & Art Programs

Crafting Funeral for Flaca: On DIY Publishing & The Power of Your Voice

Thursday, Oct. 5, 2023, 4 p.m.-5 p.m. at Psych Auditorium 105

Portland-based Chicana author Emilly Prado delves into the creation process for her award-winning book Funeral for Flaca, which debuted as a handmade chapbook before it was published and expanded by the press, Future Tense Books. She’ll share the various stages of the process including writing, research, revision, and artistic collaborations, as well as the importance of self-advocacy and intersectionality in publishing, particularly for writers of marginalized identities. Plus, hear Emilly give a reading from her book, have some snacks, and get inspired for the upcoming Reed Zine Fest in March 2024!

Risograph Workshop with Timme Lu (students only & registration-based)

Thursday, November 2, 2023, 3 p.m.- 6 p.m. at the Visual Resources Center L42

Learn Risograph printing techniques from Portland-based artist Timme Lu! Lu is a Portland-based book artist, printer, and furniture maker. They will be introducing the basics of the Risograph, a new printing duplicator in the Visual Resources Center that is available to students, and will lead an engaging group activity. Risograph printing experience is not required.

Afro-Punk Documentary Screening & virtual visit with James Spooner Thursday, February 29, 2024, 7 p.m.-9 p.m. at PAB Music Room 320

Watch the award-winning documentary Afro-Punk about the Black punk experience and history of Afro-Punk in the United States. Virtually meet the Afro-Punk festival co-founder, director and author James Spooner.

Risograph Workshop with Timme Lu (students only & registration-based)

Thursday, March 21, 3 p.m.- 6 p.m. at the VRC

Learn Risograph printing techniques from Portland-based artist Timme Lu! Lu is a Portland-based book artist, printer, and furniture maker. They will be introducing the basics of the Risograph, a new printing duplicator in the Visual Resources Center that is available to students, and will lead an engaging group activity. Risograph printing experience is not required.

Drop-in RISO Printing (students only)

Mon, March 25-Fri, March 29, 12 p.m.-4 p.m. at the VRC

Need to print a zine cover or an 8-page mini zine? Drop into the VRC to print your zine cover or 8-page mini zine on the Risograph. Limited to two colors! No appointment is needed.

IPRC Tour & Zine Making Open Hours

Tue, March 26, 5 p.m.- 9 p.m. at IPRC

Looking to put the final touches on your zines just in time for the upcoming Reed Zine Fest? Join us for a tour of the Independent Publishing Resource Center (IPRC) followed by an open-hours zine-making session (supplies provided)! Learn about the IPRC’s studio, resources, Zine Library, and programs that have supported the creative community throughout Portland for the last 25 years. Don’t miss this last-minute chance to complete your zines, learn about the IPRC, and connect with Portland’s zine community!

Printing fees will be waived for Reed College students. Masks are required at the IPRC.

Drop-in Zine Printing (students only)

Tues, March 26, 12PM-2PM at the Library Reference Desk

Wed, March 27, 12PM-2PM at the Library Reference Desk

Need to print black and white pages from your zine only? Visit the Library Reference Desk to print your zines for free. Limit on the number of copies of TBA.

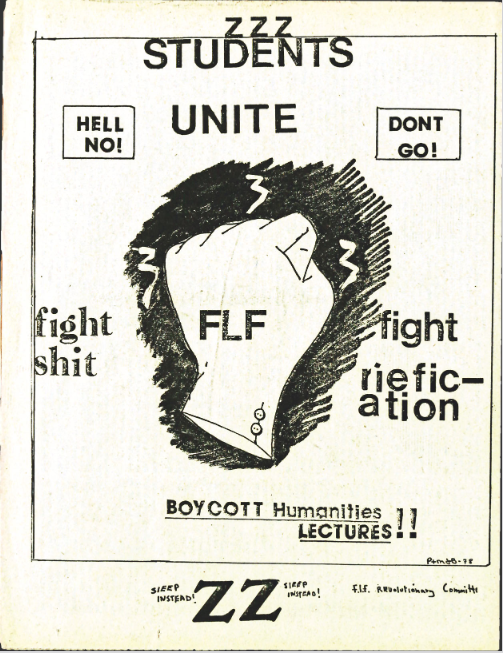

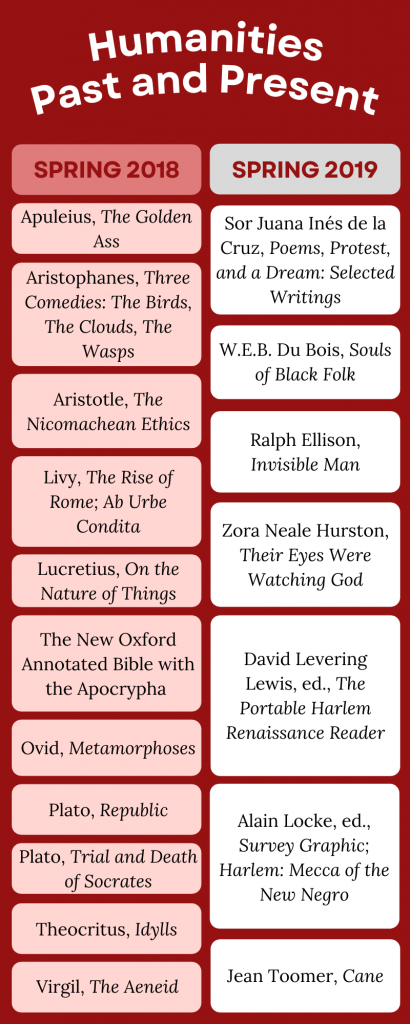

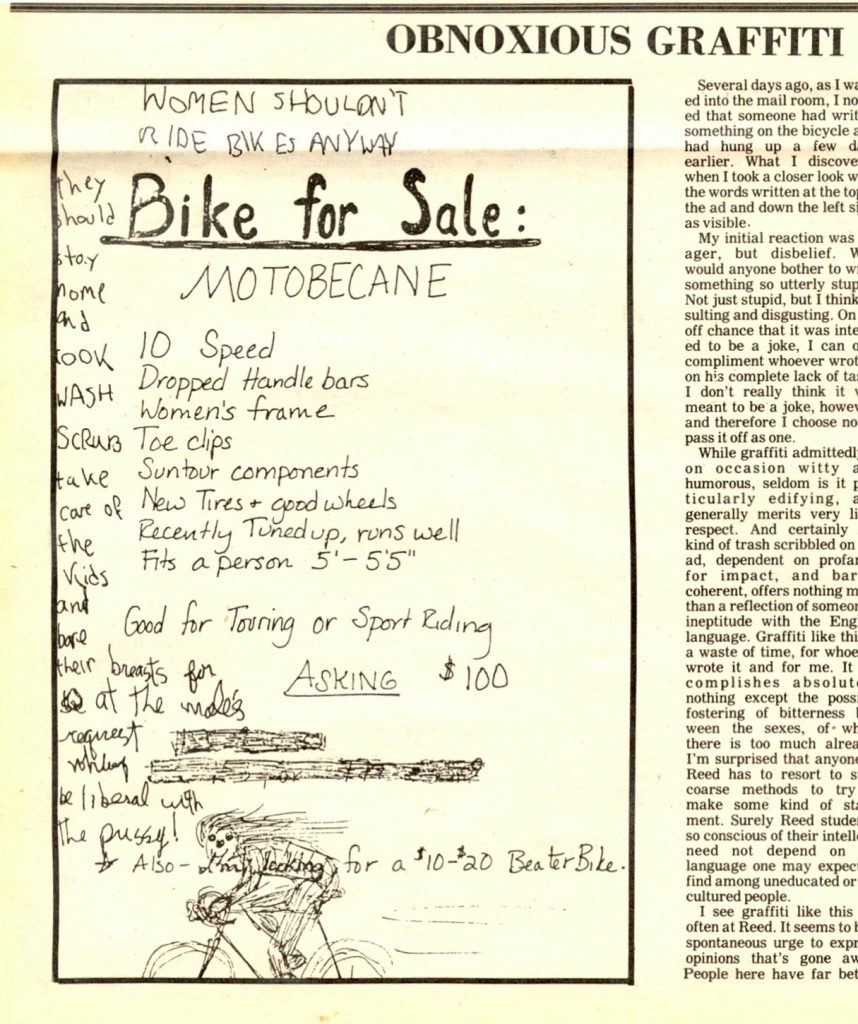

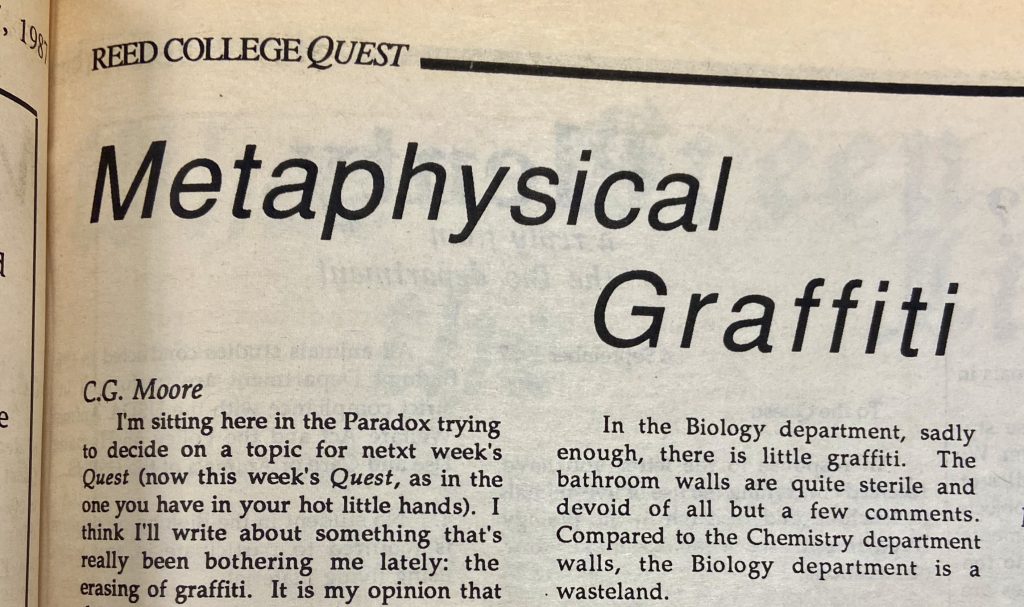

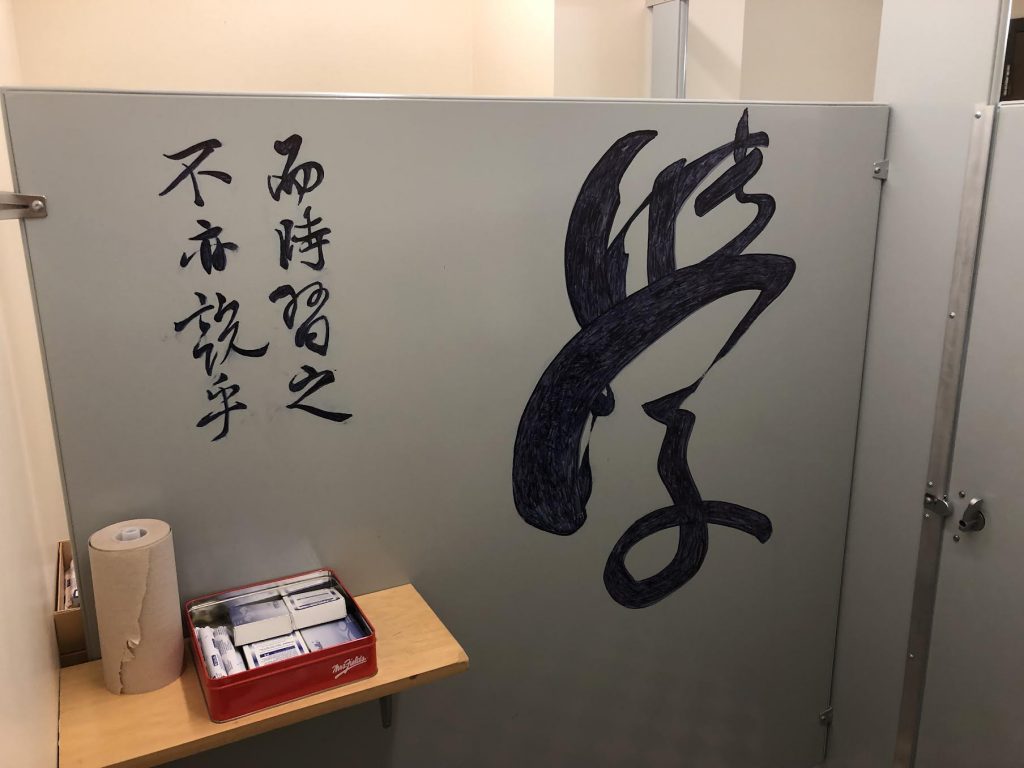

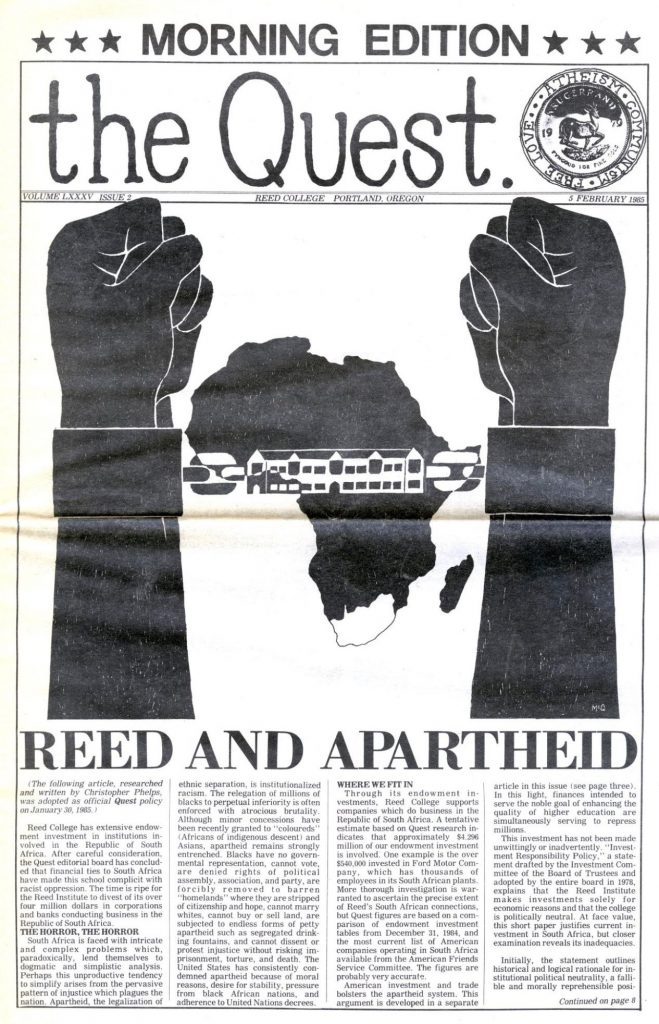

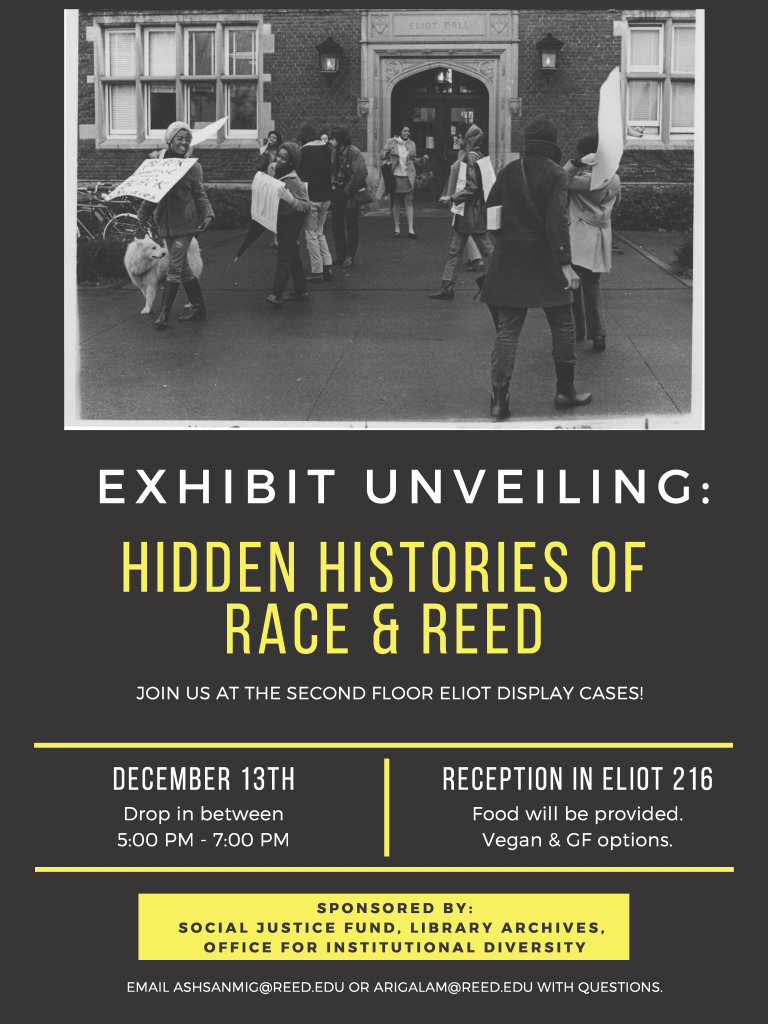

Unfurling: Zines, Art, Activism and Archiving

Thurs, March 28, 1 p.m.- 4 p.m. at Special Collections & Archives

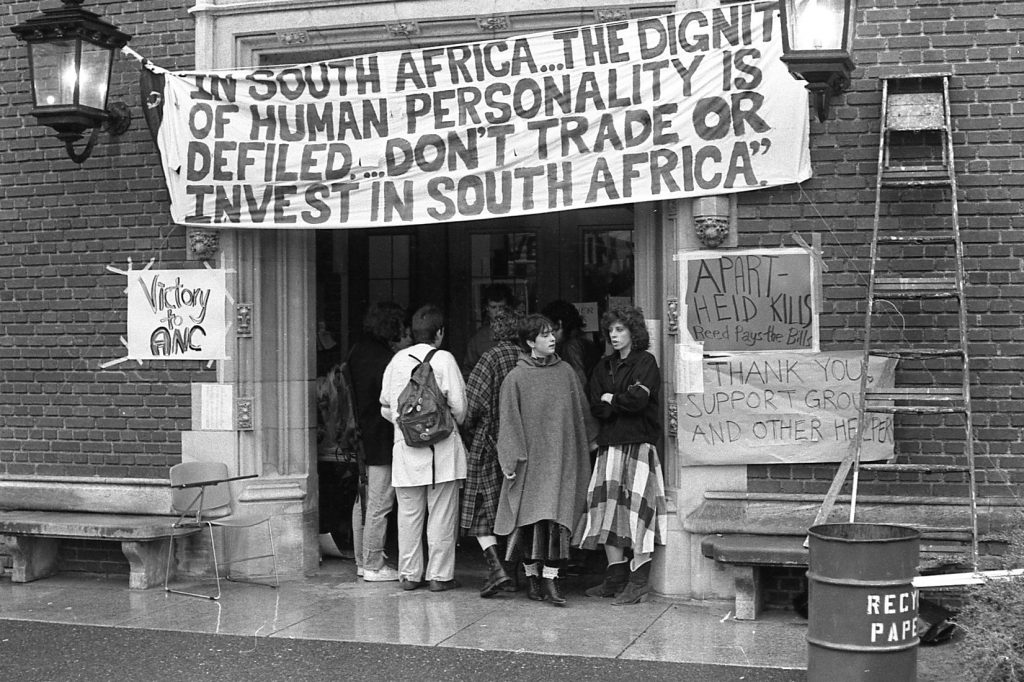

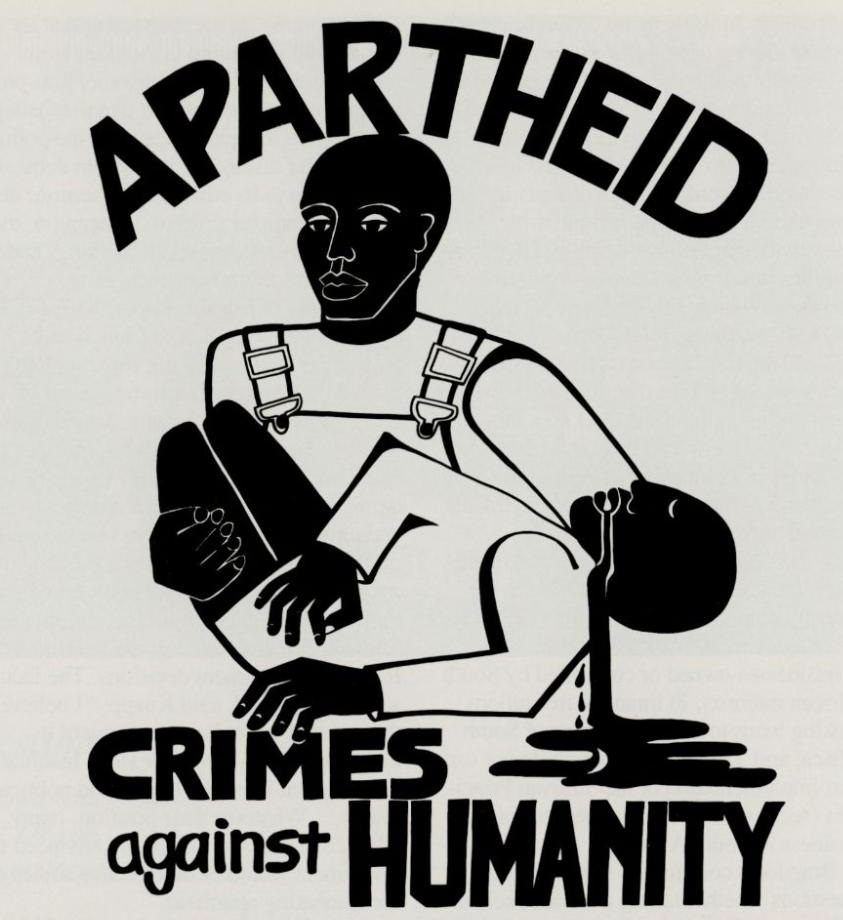

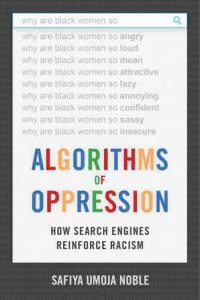

Drop into the archives as we delve into the exploration of art and activism through zines, highlighting the works of Reedies, regional artists, global artists, and activists from the Reed College Special Collections and Archives.