by John Sheehy ’82

This fall, Oregon State University Press will publish a book drawn from the Reed Oral History Project entitled Comrades of the Quest: An Oral History of Reed College. The following excerpt from the book features the voices of students and academics who found their way to Reed in the 1920s and 1930s. It offers a sense of the socio-economic and cultural diversity of students at the time–many of them first-generation college students from small towns and farms–and also highlights some of the qualities of Reed College that attracted them.

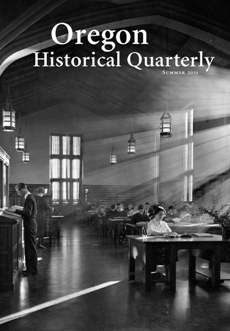

You may order the full article in the summer issue of Oregon Historical Quarterly online.

Excerpt:

REED COLLEGE’S character–and its aspiration to be among the most intellectually demanding schools in the country–was already well established by its launch in 1911. William Trufant Foster, Reed’s first president, sought to make critical thinking the holy grail of the educational experience. He believed that if Reed was to be relevant in an educational landscape dominated by specialized research universities, it would be essential to impart to students the most rigorous possible set of intellectual skills and attitudes for informing every area of inquiry. In doing so, he worked to establish a new kind of college, one that would give renewed vitality to the liberal arts while preparing its graduates for the ever-widening dimensions of the modern world.

To insure the highest standards of intellectual rigor, Foster imposed a number of curricular hurdles, including a senior thesis and orals exam. To instill self-discipline and discourage students from working for grades instead of for learning, after 1915, professors gave no grades except on request after graduation. To stress democracy and inclusiveness, Foster banned fraternities and sororities as well as the sideshow amusements of intercollegiate sports. To ensure small, intimate classes, he adopted a ten-to-one student-to-faculty ratio and directed professors to focus on teaching, not research. Finally, to promote intellectual freedom and better capture students’ enthusiasm, Foster established a free electives curriculum.

Foster assumed the presidency of Reed at age thirty-one, having just completed his doctorate at Columbia University’s Teachers College under the influence of John Dewey. He and many of the young faculty he recruited from the East Coast were adherents of pragmatism, a distinctly American philosophy that flowered at the beginning of the twentieth century. Advanced largely by the efforts of Dewey and philosophers Charles Peirce and William James, pragmatism had as its essential premise skepticism toward ideologies. Ideas were to be viewed not as immutable truths but as contingent and adaptable responses to the environment–tools people could utilize in coping with the world around them. This approach had a liberating effect on a generation of jurists, journalists, policymakers, and academics who created the progressive movement. Freed from fatalistic nineteenth-century determinism, progressives sought scientific solutions to social problems in a universe they viewed as still in play, where people were the agents of their own destinies.

Accordingly, Foster endeavored to involve the new college in the social and cultural reforms taking place in Portland during the 1910s. Reed faculty served on art commissions, public library committees, health bureaus, and city planning commissions and, along with students, volunteered for good-government organizations that addressed vice, delinquency, and sexual hygiene. They advocated for the eight-hour workday, minimum wage laws, and unemployment insurance. By 1917, the college was also enrolling 55,000 local citizens annually in free extension classes around town.

In Portland’s conservative quarters, however, the college was developing a reputation for arrogant self-righteousness and radical social initiatives. Foster’s outspoken opposition to America’s entry into World War I in 1917 inflamed pro-war conservatives, resulting in the local press denouncing the college as a hotbed of sedition and socialism. During the Red Scare that immediately followed the war, Portland critics branded Reed’s heterodoxy and progressive nature with the derogatory slur, “Communism, atheism, and free love,” a label that would stick in the public imagination for decades to come. An erosion of local financial support subsequently led to the college’s financial collapse and Foster’s resignation in 1919.

Foster’s successor, a history professor from the University of Washington named Richard Scholz, joined the college in 1921 with hopes of renewing its initial promise. One of the nation’s first Rhodes scholars, Scholz sought to institutionalize Foster’s academic rigor by replacing the electives curriculum with a prescribed core curriculum he called “new humanism.” Intended to be a “unified reinterpretation of the whole of existence,” new humanism was Scholz’s antidote to the disillusionment and disintegration left in the wake of the First World War. Anchored by a one-year humanities program required of all freshmen, Scholz’s initiative was in the vanguard of a number of general educational courses spawned during the political upheavals of the 1930 and 1940s. Columbia University led the way, establishing for all freshmen in 1919 its famous Contemporary Civilization course, an amalgam of modern economics, government, philosophy, and history.

Unlike Columbia’s course, which during its first ten years covered no material before 1871 and restricted students to reading textbooks, Scholz’s humanities program offered parallel courses in literature and history that extended from the Greeks to 1763 and relied heavily on the use of primary texts. And while Scholz employed the classics as a means of providing students with a common intellectual culture and language, his humanities program was neither a history course, as was the case of many Western Civilization courses then emerging, nor a prescribed curriculum of overriding metaphysics, as John Dewey criticized the University of Chicago’s Great Books program as being. Humanities at Reed was primarily an exercise in inquiry and in the discovery of a student’s critical reason, emotional sensitivity, imagination, and judgment, shaped and tested through writing, small group discussion, and individual conferences.

Reed history professor Reginald “Rex” Arragon, who directed the humanities program from Scholz’s death in 1924 until 1962, believed the humanities program fell within the practice of Dewey’s “learning by doing,” employing ideas as instruments to solve problems. Dewey’s scientific practice of observation–inquiring and experimenting, then distinguishing, analyzing, relating ideas, and drawing conclusions–fit with Arragon’s view of disciplined critical thinking as both the means and the significant end of the humanities. “Doing” was a matter of reasoning. To substitute metaphysics for this scientific method, Arragon believed, was to arrest the rational, intellectual process. Outcomes largely supported that belief. During the 1920s and 1930s, Reed had the highest percentage of graduates in the country going on to earn advanced degrees, more than double the

nearest competitor.

During the college’s first three decades, 80 percent of the Reed student body was drawn from the Pacific Northwest, the majority from Portland. That homogeneity would begin to change after the Second World War, when the G.I. Bill brought a more geographically diverse mix of students to Reed. Part of Reed’s local appeal during its early decades stemmed from the fact that it and the University of Portland–an all men’s Catholic college at the time–were the only colleges in Portland until the late 1930s, when Albany College relocated to the city from Albany, Oregon, and renamed itself Lewis & Clark College. Reed was an attractive choice for students looking to save money by living at home. During the 1920s, for example, only half of the three hundred students enrolled at Reed lived on campus.

With the onset of the Great Depression in the 1930s, Reed’s student enrollment, like that of many schools, dramatically increased; college became a refuge for young people unable to find a job. That trend dramatically expanded in 1935, when the federal government instituted a “work study program” under the National Youth Administration, paying students up to forty cents an hour for work on campuses. Disadvantaged students were able to work for their tuition and avoid paying room and board by living at home. While Reed’s enrollment steadily increased during the 1930s, from three hundred students to over five hundred, student residency dramatically dropped to the point where, by the mid 1930s, 86 percent of Reed students were local “day-dodgers” who commuted daily to campus, leaving the dormitories partially empty.

Self-selection and a high attrition rate–distinguishing characteristics of Reed’s student body at the time–resulted in a student culture on campus increasingly marked by intense intellectualism, social nonconformity, and a sense of self-imposed isolation from the surrounding local community, despite the high percentage of commuter students. By the 1930s, Foster’s quest for rigorous critical thinking that had given Reed much of its original vitality had become institutionalized on campus as a challenge to all manner of status quo thinking, serving to attract young freethinkers from around the Pacific Northwest.

THE YEAR 2011 marks Reed College’s centennial. As a gift to the college, the Reed Alumni Association launched the Reed Oral History Project in 1998 to capture and preserve the experiences of students, faculty, administrators, and trustees during the college’s first century. Trained alumni volunteers under the direction of Oregon oral historians Donna Sinclair and Cynthia Lopez as well as Bancroft Library archivist Lauren Lassleben ’75 collected nearly four hundred individual oral histories and interviewed more than one thousand other alumni in facilitated group interviews. Dozens of legacy interviews conducted as far back as 1935 by longtime Reed professor and noted Northwest historian Dorothy O. Johansen also were added to the collection.

Oral history differs from other forms of memory collection, such as memoir or journal writing, in that it arises from dialog between an interviewer and an interviewee. That dialog turns on both memory and inquiry. In the case of the Reed Oral History Project, the interview questions sought a connection between an individual’s personal biography and his or her role in the college’s collective history. Interviewers approached individuals with a list of open-ended questions designed to explore personal, cultural, academic, and institutional experiences with the college. During the actual interviewing process, however, they were trained to follow whatever memory stream the individual chose to pursue regarding Reed. Oral history theorist Alessandro Portelli calls this process history-telling–a cousin to storytelling–because of its thematic scope and dialogic nature. “Memory is not just a mirror of what has happened,” notes Portelli, “it is one of the things that happens, which merits study. Oral sources tell us not just what people did, but what they wanted to do, what they believed they were doing, and what they now think they did.”

College stories are a recognized thematic genre in themselves, with specific motifs, themes, and mythic roles that are the stuff of films, biographies, and literature–the stern but nurturing professor, the student’s coming of age, the triumphant breakthrough of personal discovery. But oral history, in that it plumbs personal memories, can often feature other roles and motifs of the college experience that are similar but less commonly recognized. Reed College, with its historic nonconformity and idiosyncratic lack of fraternities and sororities, issued grades, intercollegiate athletic teams, and homecoming events, provides a unique collective memory that is perhaps well served by the benefits of oral history.

You may order the full article in the summer issue of Oregon Historical Quarterly online.