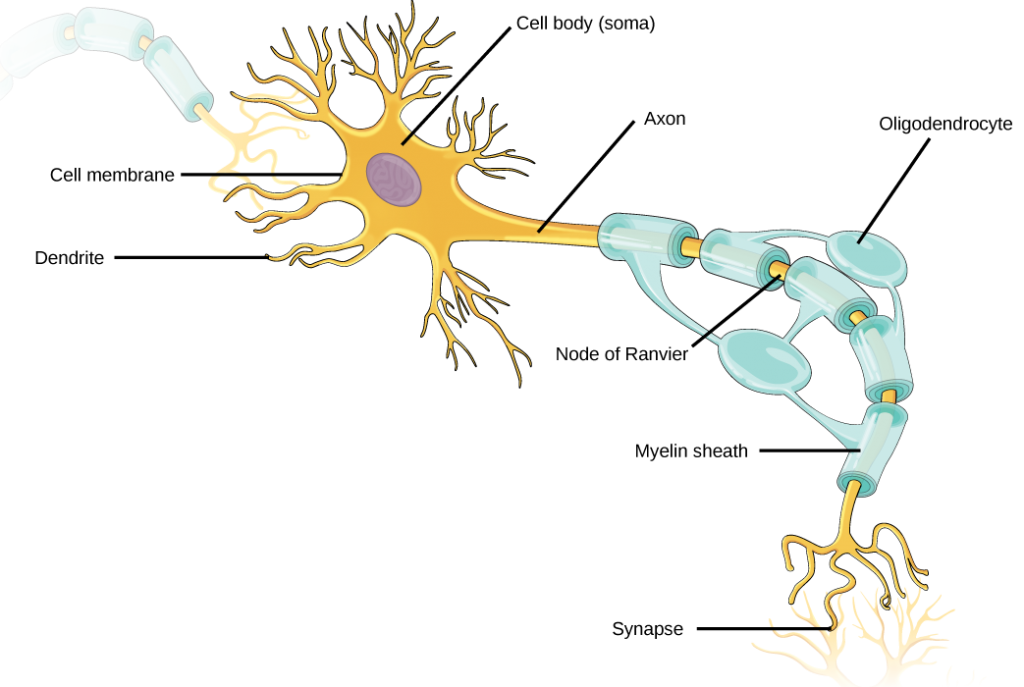

Neurons make up your brain and nervous system and allow you to think and move. A neuron is a single cell in this system. Neurons are long cells that are able to move signals throughout the body using an electrical chemical gradient (a property that is described broadly as bioelectricity and forms the basis of nervous system evolution). The longest neuron in your body reaches from the base of your neck to your toe. An average neuron has a cell body or soma that is surrounded by tendrils called dendrites that receive signals from surrounding cells. Once the signal is received, it is sent down a long branch called an axon. The axon may be protected through an extra layer called a myelin sheath. The axon will be in contact with another neuron at the synapse. This connection allows the signal to be continued.

How these neurons are made and form connections in both development, healing from damage, and normal growth is a constantly evolving field. Several questions have guided the field: How are new neurons made?; How do axons grow?; and How do neurons form connections with each other?

Information travels from the dendrites, which receive a signal, and then relay that information along the axon. The myelin sheath speeds the conductance of the electrical signal, eventually activating synapses to continue sending the message. Figure 16. 3 from https://opentextbc.ca/biology/chapter/16-1-neurons-and-glial-cells/

Neurogenesis: how neurons are made

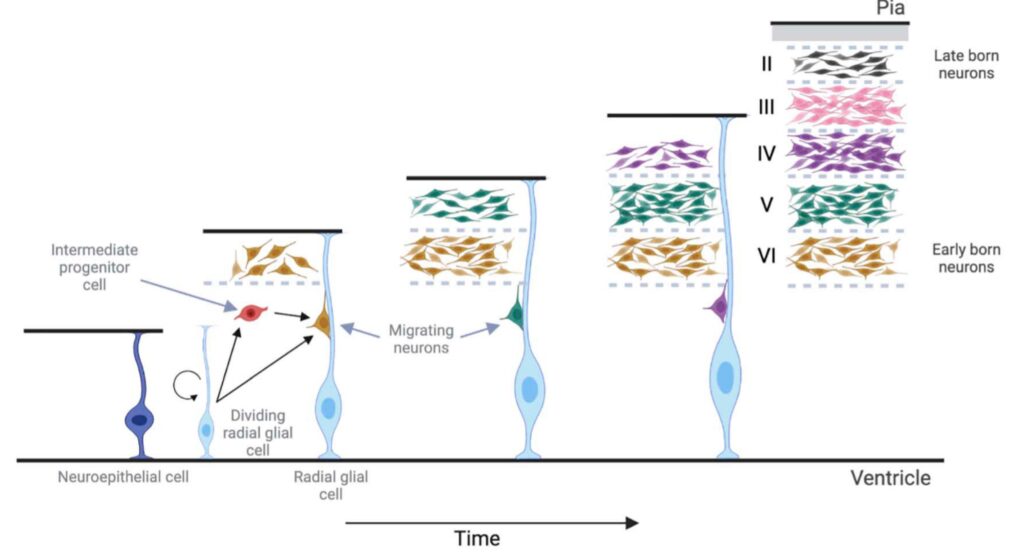

Neurons are made from radial glial cells, a type of stem cell. A stem cell is a type of cell that has the potential to grow into many different types of cells. Radial glial cells are located in the developing cerebral cortex. They are long and extend from the ventricular surface (inwards) to the pial surface (outwards). These progenitor cells will divide asymmetrically, with each daughter cell receiving different signals. These signals can cause the newly divided cells to differentiate into a neuron, or remain a radial glial cell. Differentiated cells will migrate outward toward the pial surface to become fully differentiated neurons. As these cells divide, a select number of radial glial cells will be maintained so more neurons can be produced. This is true for many other types of stem cells (see figure below). In the adult brain, a population of radial glial cells is still maintained, allowing new neurons to be made throughout adult life.

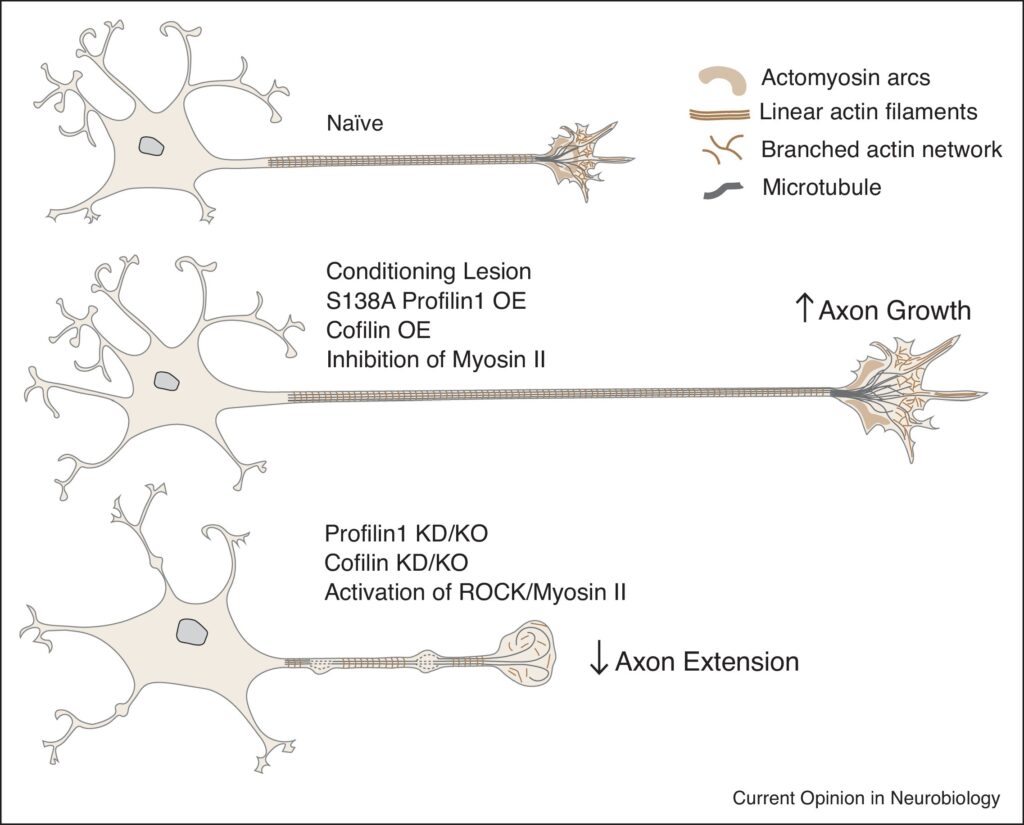

When a neuron receives a signal from a neighboring neuron, the signal is sent down the axon to the next neuron. Axons can be very long, some traversing your whole body. When a new neuron is created, its axon must find the correct neighboring neuron. This is done through complex signaling pathways that tell the neuron where to go. The tip of these growing axons are called growth cones. These dynamic structures change based on the surrounding environment, guiding the axon to its desired location. The growth cone contains many different cytoskeletal structures and proteins. A cytoskeleton gives structure, shape, and movement to the cell. It contains many different types of proteins. One such structure located on the growth cone is filopodia. Filopodia are made out of actin, a type of protein. Regulators of actin create dynamic filopodia that can be destroyed and reformed to change direction in axonal growth. This is one example of a structure that can be formed in a growth cone. Once the growth cone has reached the right location, it receives signals for the destruction of the growth cone, stopping axon extension and allowing a connection to be formed.

Cytoskeletal elements highlighted. Image of a naive neuron undergoing no growth (upper panel). A neuron that is experiencing axon growth in response to damage moduled of spinal cord damage. From Leite et al. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conb.2020.11.015

Synaptogenesis: how neurons form connections with each other in a developing brain

Synapses are sites where neurons form connections with each other and allow signals to travel from neuron to neuron. Importantly, they transform the electrochemical signal from an axon into a chemical signal in the form of neurotransmitters. They are then able to take the signal of a neurotransmitter into an electrochemical signal again. As the signal travels down the neuron, it reaches the presynapse. This is in very close proximity to the next neuron postsynapse. This small cleft is where neurons communicate with each other by sending signals through neurotransmitters. In development, growing axons will come into contact with their desired neuron. This will trigger the development of a synapse. In the presynaptic and postsynaptic ends, a prerequisite to the formation of the neuron is the presence of the necessary proteins to make a functioning synapse. These components are often trafficked to the synaptic ends before the formation of a synapse. This allows for the quick formation of synapses. Humans are particularly good at forming synaptic connections.

References:

- Agirman, G., Broix, L., & Nguyen, L. (2017). Cerebral cortex development: An outside-in perspective. FEBS Letters, 591(24), 3978–3992. https://doi.org/10.1002/1873-3468.12924

- Agrawal, M., & Welshhans, K. (2021). Local Translation Across Neural Development: A Focus on Radial Glial Cells, Axons, and Synaptogenesis. Frontiers in Molecular Neuroscience, 14, 717170. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnmol.2021.717170

- Leite, S. C., Pinto-Costa, R., & Sousa, M. M. (2021). Actin dynamics in the growth cone: A key player in axon regeneration. Current Opinion in Neurobiology, 69, 11–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.conb.2020.11.015

- Qi, C., Luo, L.-D., Feng, I., & Ma, S. (2022). Molecular mechanisms of synaptogenesis. Frontiers in Synaptic Neuroscience, 14, 939793. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnsyn.2022.939793

- Chapter 16, Neurons and Glia. https://opentextbc.ca/biology/chapter/16-1-neurons-and-glial-cells/

Content written and collated by Kyle Rowan, Reed’24.