- Electrochemical Signaling and Origins of the Neuron

- To explain the development and evolution of the human brain, which may comprise the most sophisticated central nervous system in the animal kingdom, we must first examine how nervous systems evolved in general.

- To do that, we must start with the evolution of the first neurons. So, what is a neuron, anyway? Common characteristic traits such as the ability to generate action potentials are shared with other types of cells, like muscles and skin. A clue that all these cells can derive from a common ancestor can be found during every individual’s development when nervous tissue differentiates from the early population of epithelial stem cells that also become skin and muscle.

- The simplest working definition of a neuron is a cell that transmits information from one cell to another via electrochemical signals (Kristan, 2016).

- Electrochemical meaning either electrically charged ions that inform by directly changing the voltage across a cell membrane by their movement or chemicals that are recognized by and bind to specific receptors on a membrane to cause various effects.

- The ability for cells to communicate with each other in a cooperative manner by electrochemical signals is far older than multicellularity, as even single-celled eukaryotes are able to use these most basic mechanisms to communicate and cooperate with other members of their same species in the simplest ways (these abilities also providing precursors to true multicellularity). These single-celled organisms already possess enzymes for producing, releasing, and responding to transmitters, these components being the precursors to the neural synapse (Kristan, 2016).

- Genes and proteins similar to those that are considered “neuron-specific” can even be found even in bacteria, suggesting their presence in a common ancestor of prokaryotes and eukaryotes as long as 4 billion years ago (Kristan, 2016).

- Unicellular eukaryotes such as choanoflagellates (the closest living relatives animals) aggregate into colonies that transmit signals between each other to synchronize movements of flagella amongst the whole colony; sponges, the simplest multicellular animals, use a similar mechanism to regulate flagellar movement and control the flow of water through their central cavities (Kristan, 2016).

- In the generation and transmission of the action potential, the three most important ions are potassium, sodium, and calcium. Evidence suggests that the voltage-gated potassium channel evolved first in the common ancestor of all animals, and the calcium and sodium channels were later created by gene duplications followed by mutations that made them selective for different ions; once in possession of at least two different types of ion channels, their gradients can then be used by single-celled organisms to regulate simple behaviors like control of cilia (Kristan, 2016). Adding the third ion then provides a free variable that can be used for much more finely tuned regulation and control of cellular processes.

- Video on resting membrane potential: https://learninglink.oup.com/access/content/neuroscience-sixth-edition-student-resources/animation-2-1

- Video on action potential: https://learninglink.oup.com/access/content/neuroscience-sixth-edition-student-resources/animation-2-3

- Freely moving animals began to control their behaviors by connections between epithelial cells transmitting signals that could be stimulated by cells capable of sensing the environment; as they increased in size, the distinction between cells inside the body and cells at the body’s surface exposed to the environment became more important, and interior cells become specialized for more rapid conduction; eventually, the network of electrochemically connected proto-neurons inside the body became fully distinct from the other cells to which they ultimately communicated (Kunta, 2016).

- Thus the first true nervous systems were born: systems of cells in organisms that detect stimuli and then transmit an appropriate signal through the body until it reaches cells that carry out stereotypical behaviors in response.

- Swanson (2012), p. 28-40 has more info on emergence of sensory, motor, and interneurons to form primitive circuits in nerve nets.

- The differences between the nervous systems in ctenophores and cnidarians furthermore suggests that these nervous systems may have independently evolved twice (Kristan, 2016 and Singer, 2019).

- This figure (from Ryan, 2014) shows a phylogeny of animals with nervous systems or neuron-like precursors to nervous systems. Ctenophora appear far removed from the cnidarians and

- bilaterians.

- That these “diffuse” nervous systems still exist today as “living fossils” in forms of life like jellyfish that have persisted for hundreds of millions of years demonstrates the robust capability of a nervous system with even so little capacity.

- An example of a task performed by these that requires relatively complex integration of information is that the sea anemone Calliactis is able to tell the difference between a mollusk shell that is full of a mollusk and a partially empty shell occupied by a smaller hermit crab, so that it can move only onto the crab-occupied shells (Erulkar, 2014).

- This figure (from Pallasdies, 2019) provides a diagram of the nervous system of a species of jellyfish, showing how input from the sensory rhopalia is transmitted to muscles.

- Another figure of a cnidarian nervous system (Erulkar, 2014).

- From Simple Nervous Systems to Central Nervous Systems

- Ganglia and radial symmetry

- In the nerve nets, pathways from sensory input to motor output are generally very simple. The next step in evolution of the nervous system, therefore, is aggregation of neurons into more complex units known as ganglia.

- While jellyfish are technically radially symmetric, organisms such as starfish are good examples of what radial symmetry looks like with a more sophisticated ganglia: a nerve ring.

- (Figure from Lumen Learning, 2023)

- Advantages: while not yet achieving the centralization of a true head (cephalization), the nerve ring concentrates nervous tissue around one of the most important sensory organs, the mouth.

- Disadvantages: a centralized nervous system is more vulnerable to damage; while starfish can regenerate lost limbs, most require an intact oral nerve ring and partial radial nerve up to the wound site (Huet, 1975).

- (Figure from Lumen Learning, 2023)

- Bilateral Symmetry and cephalization

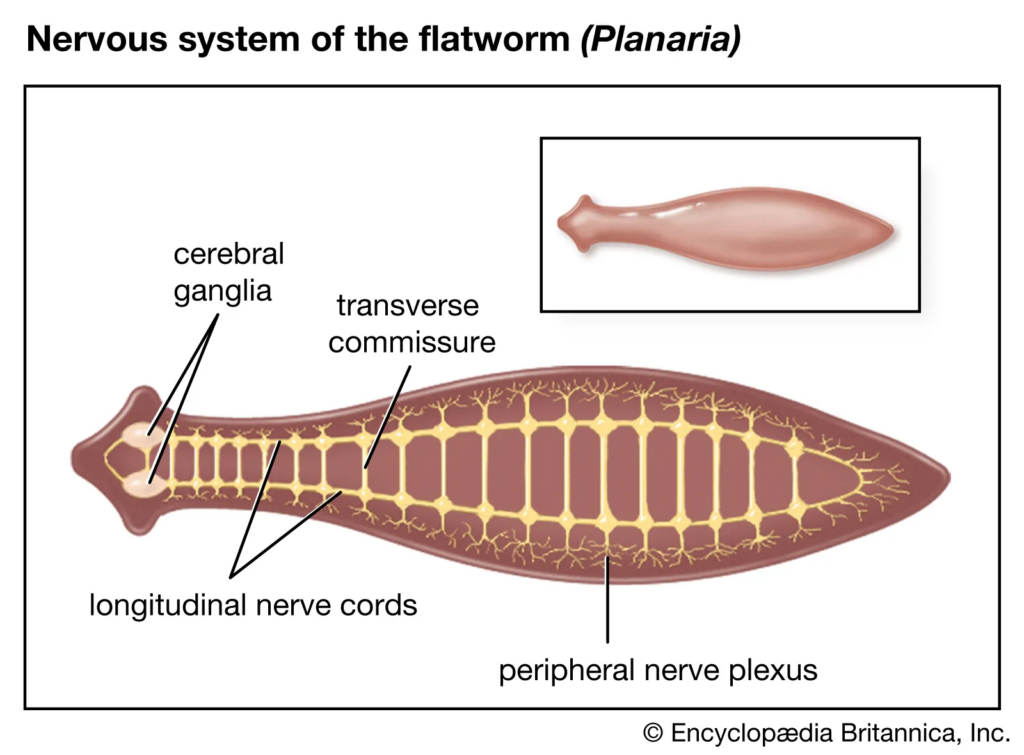

- The planaria (flatworm) is the simplest animal with bilateral symmetry, gradients of gene expression enabling cephalization, and an aggregate of neural cells in the head forming a bilobar brain (Sarnat, 2002).

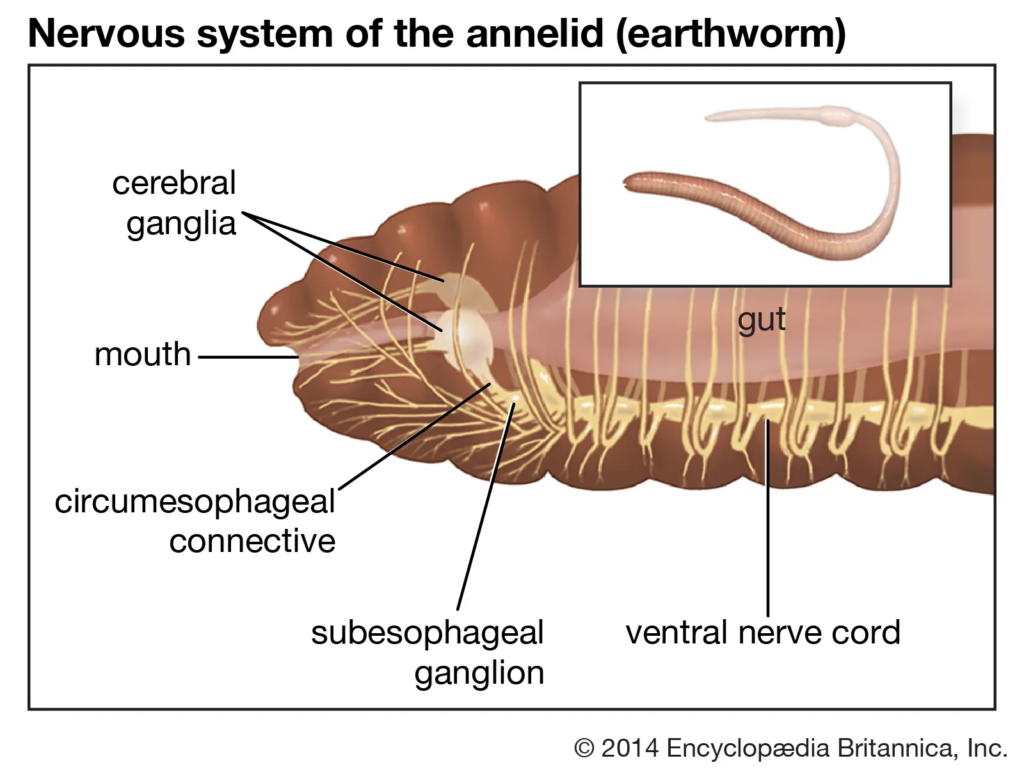

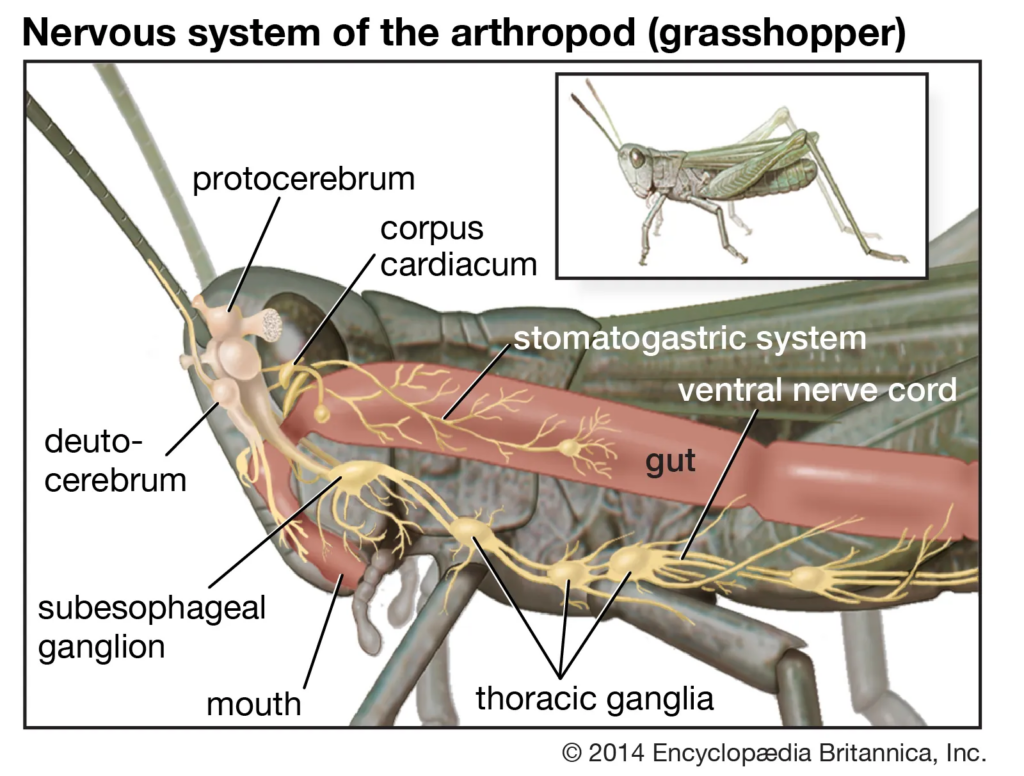

- Cephalization and complexity increases between invertebrates; figures from Erulkar (2014).

- In the case of the grasshopper, the relationship between cephalization (more cerebral nervous tissue) and proximity to sensory organs (mouth, eyes, and antenna, which are themselves mutually proximate) is evident.

- Less distance to travel = faster signal processing.

- More advanced cerebrums are also less stereotyped, with neural plasticity allowing for learning, memory, and emergence of complex behaviors like planning.

- At some point, this becomes sufficient to produce within an organism the phenomena of conscious experience. At present, it is generally agreed that all vertebrates and many invertebrates (such as cephalopods [octopuses and squids], but even arthropods [insects, arachnids, and crustaceans]) are conscious and sentient (self-aware of feelings) (Animal Ethics, 2023).

- Ganglia and radial symmetry

- Chordates and Vertebrates

- Evolution of the notochord (and eventually, vertebrae) enabled more efficient locomotion (Swanson, 2012, p. 60).

- Despite increasing cephalization, ganglia in the spine retain autonomous function. E.g., the pain withdrawal reflex (figure from Cornell, 2016) reacts before the signal reaches the brain to be consciously processed.

- There is a lot that can be said about embryology between vertebrates.

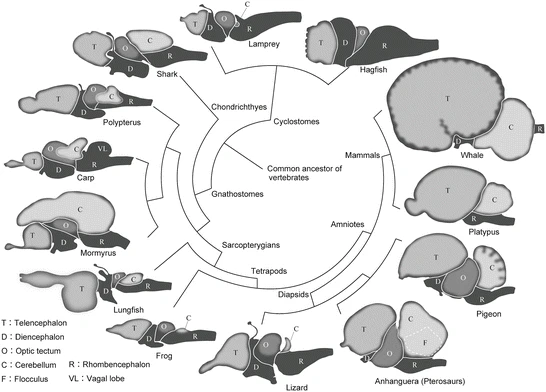

- Amongst the vertebrates, the warm-blooded birds and mammals have the largest brains, and notably the largest cerebral cortices / telencephalon (figure from Murakami, 2017).

- Cold-blooded vertebrates in cold climates have brains several times smaller than cold-blooded vertebrates in tropical climates (Yu, 2014).

- The metabolic costs of encephalization and large brains makes organisms much more vulnerable to hypoxia (Sukhum, 2016).

- In summary, large brains consume lots of energy and need to be kept warm to function.

- Archaic Hominids and Modern Humans

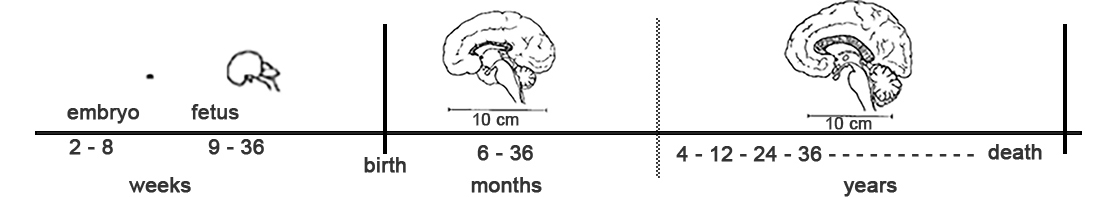

- Brain size continued to increase among the primates, ultimately ending with modern humans.

- The most significant areas of growth relevant to improved cognition are the cerebrum and in particular the prefrontal cortex.

- Brain size is not an absolute predictor of intelligence. Whales and elephants have larger brains than humans, and while they are smarter than most mammals, they do not seem to beat us in any particular way.

- Neanderthals also had slightly larger brains than modern humans, but are not believed to have been as intelligent.

- Hominid hunting strategy required elaborate social cooperation, which selected for increased intelligence (to serve long term planning, transmission of intergenerational cultural knowledge, use of language, navigation of abstract social roles, etc.). It is worth noting that this hunting strategy also selected for us to be ranked best amongst animals and other primates in features other than intelligence, such as ability to cool the body by sweating, which helps to run long distances with endurance (until prey is exhausted), and our shoulder structure is also optimized to throw objects like spears with power and accuracy.

- The combination of the intrinsically favorable environmental conditions of the holocene epoch and the development of technologies like clothing and fire to make the environment even more hospitable and food more calorically efficient allowed hominid populations to expand and migrate ‘out of Africa’.

- At a certain point, the greatest source of competition and therefore selection became not the environment per se, but other groups of intelligent hominids.

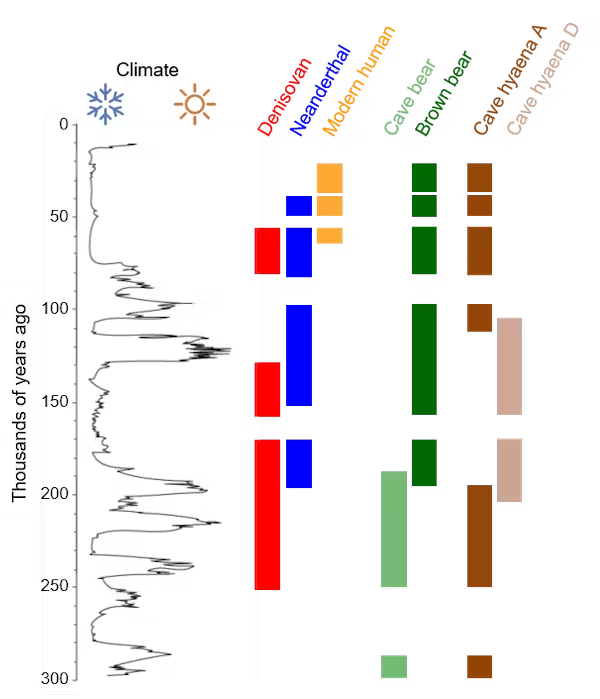

- Modern humans both fought with and interbred with archaic hominid populations (Neanderthals, Denisovans), but ultimately our group, the most recent to leave Africa and apparently the most intellectually advanced, became dominant and drove others extinct. Hunting by hominids also contributed to the extinction of various megafauna after the last ice age.

- Within the eponymous Denisova Cave, there is evidence modern humans, Neanderthals, and Denisovans may have inhabited simultaneously about 50,000 years ago (Zavala and Roberts, 2021).

- Brain size continued to increase among the primates, ultimately ending with modern humans.

- The fossil remains from Denisova Cave include a 50,000 year old child who had a Neanderthal mother and Denisovan father (Vogel, 2018, Warren, 2018, and Slon, 2018).

- Figure from Callaway (2016).

- Figure from Sousa, (2017).

- The amount of genetic difference between modern humans and our closest relatives is very small. In the entire genome, there are only 31,389 single nucleotide positions where all present day humans carry a novel or derived SNP compared to Neanderthals and Denisovans exclusively carrying an ancestral form; of these, 3,117 fall in regulatory regions, 32 affect splicing sites, and only 96 result in fixed amino acid replacement substitutions in just 87 unique proteins (Paabo, 2014; Table S1 has a list of every gene and mutation).

- Rest of the SNPs are apparently silent and do not affect gene expression.

- There is not a single novel protein or gene that is unique to humans?

- A different study (Kuhlwilm, 2019) found 571 genes with non-synonymous changes “at high frequency” (less strict definition than Paabo).

- Three substitutions in two proteins (KIF18a and KNL1) are involved in kinetochores which segregate chromosomes during cell division; the human versions of these elongate metaphase and result in fewer segregation errors in the developing neocortex (Mora-Bermudez, 2022).

- FOXP2 has received much attention for its involvement in language and speech disorders, but it was actually identical in archaic humans, has homologs in other mammals, and thus might not be special to human evolution (Fisher, 2019).

- Other archaic genes are preserved in specific human ethnic groups and appear to offer some advantages (Singer, 2020).

- References

Animal Ethics. (2023, March 11). What beings are conscious?. Animal Ethics. https://www.animal-ethics.org/what-beings-are-conscious/

Callaway, E. (2016, February 18). Evidence mounts for interbreeding bonanza in ancient human species. Scientific American. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/evidence-mounts-for-interbreeding-bonanza-in-ancient-human-species/

Cornell, B. (2016). Reflex Arcs. BioNinja. https://ib.bioninja.com.au/options/option-a-neurobiology-and/a4-innate-and-learned-behav/reflex-arcs.html

Diversity of Nervous Systems. Lumen Learning. (2023). https://courses.lumenlearning.com/wm-biology2/chapter/diversity-of-nervous-systems/

Erulkar, S. D. (2014). Evolution and development of the nervous system. Encyclopædia Britannica. https://www.britannica.com/science/nervous-system/Evolution-and-development-of-the-nervous-system

Fisher, S. E. (2019). Human genetics: The evolving story of FOXP2. Current Biology, 29(2). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2018.11.047

Huet, M. (1975). Role of the nervous system during the regeneration of an arm in a starfish: Asterina gibbosa Penn. (Echinodermata, Asteriidae). J Embryol Exp Morphol, 33(3).

Kristan, W. B. (2016). Early evolution of neurons. Current Biology, 26(20). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2016.05.030

Kuhlwilm, M., & Boeckx, C. (2019). A catalog of single nucleotide changes distinguishing modern humans from archaic hominins. Scientific Reports, 9(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-44877-x

Mora-Bermúdez, F., Kanis, P., Macak, D., Peters, J., Naumann, R., Xing, L., Sarov, M., Winkler, S., Oegema, C. E., Haffner, C., Wimberger, P., Riesenberg, S., Maricic, T., Huttner, W. B., & Pääbo, S. (2022). Longer metaphase and fewer chromosome segregation errors in modern human than neanderthal brain development. Science Advances, 8(30). https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abn7702

Murakami, Y. (2017). The Origin of Vertebrate Brain Centers. In Brain Evolution by Design: From neural origin to cognitive architecture. essay, Springer Japan.

Pallasdies, F., Goedeke, S., Braun, W., & Memmesheimer, R.-M. (2019). From single neurons to behavior in the jellyfish Aurelia Aurita. eLife, 8(e50084). https://doi.org/10.7554/elife.50084.sa2

Pääbo, S. (2014). The human condition—a molecular approach. Cell, 157(1), 216–226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2013.12.036

Ryan, J. F. (2014). Did the ctenophore nervous system evolve independently? Zoology, 117(4), 225–226. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.zool.2014.06.001

Sarnat, H. B., & Netsky, M. G. (2002). When does a ganglion become a brain? evolutionary origin of the Central Nervous System. Seminars in Pediatric Neurology, 9(4), 240–253. https://doi.org/10.1053/spen.2002.32502

Singer, E. (2019, January 25). Did neurons evolve twice?. Quanta Magazine. https://www.quantamagazine.org/comb-jelly-neurons-spark-evolution-debate-20150325/

Singer, E. (2020, May 18). How neanderthal DNA helps humanity. Quanta Magazine. https://www.quantamagazine.org/how-neanderthal-dna-helps-humanity-20160526/

Slon, V., Mafessoni, F., Vernot, B., de Filippo, C., Grote, S., Viola, B., Hajdinjak, M., Peyrégne, S., Nagel, S., Brown, S., Douka, K., Higham, T., Kozlikin, M. B., Shunkov, M. V., Derevianko, A. P., Kelso, J., Meyer, M., Prüfer, K., & Pääbo, S. (2018). The genome of the offspring of a Neanderthal mother and a Denisovan father. Nature, 561(7721), 113–116. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-018-0455-x

Sousa, A. M. M., Meyer, K. A., Santpere, G., Gulden, F. O., & Sestan, N. (2017). Evolution of the human nervous system function, structure, and development. Cell, 170(2), 226–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2017.06.036

Sukhum, K. V., Freiler, M. K., Wang, R., & Carlson, B. A. (2016). The costs of a big brain: Extreme encephalization results in higher energetic demand and reduced hypoxia tolerance in weakly electric African fishes. Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences, 283(1845), 20162157. https://doi.org/10.1098/rspb.2016.2157

Swanson, L. W. (2012). Brain architecture: Understanding the basic plan. Oxford University Press.

Vogel, G. (2018, August 22). This ancient bone belonged to a child of two extinct human species. Science. https://www.science.org/content/article/ancient-bone-belonged-child-two-extinct-human-species

Warren, M. (2018, August 22). Mum’s a Neanderthal, dad’s a Denisovan: First discovery of an ancient-human hybrid. Nature News. https://www.nature.com/articles/d41586-018-06004-0/

Yu, Y., Karbowski, J., Sachdev, R. N., & Feng, J. (2014). Effect of temperature and glia in brain size enlargement and origin of allometric body-brain size scaling in vertebrates. BMC Evolutionary Biology, 14(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12862-014-0178-z

Zavala, E. I., Jacobs, Z., Vernot, B., Shunkov, M. V., Kozlikin, M. B., Derevianko, A. P., Essel, E., de Fillipo, C., Nagel, S., Richter, J., Romagné, F., Schmidt, A., Li, B., O’Gorman, K., Slon, V., Kelso, J., Pääbo, S., Roberts, R. G., & Meyer, M. (2021). Pleistocene sediment DNA reveals hominin and faunal turnovers at Denisova Cave. Nature, 595(7867), 399–403. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03675-0

Zavala, E., Meyer, M., Roberts, R., & Jacobs , Z. (2023, March 9). Dirty secrets: Sediment DNA reveals a 300,000-year timeline of ancient and modern humans living in Siberia. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/dirty-secrets-sediment-dna-reveals-a-300-000-year-timeline-of-ancient-and-modern-humans-living-in-siberia-161585