Laura Arnold Leibman’s academic article Jewish Healers and Yellow Fever in the Eighteenth Century Americas explores how members of the Jewish community have historically contributed to helping others during health crises while challenging harmful stereotypes surrounding Jews and their relation to pandemics. While many academics have acknowledged that antisemitism has fueled rhetoric linking Jews to disease, Leibman argues that pandemic related prejudices are often rooted in even deeper fears surrounding the legitimacy of Jewish citizenship within the Americas. Without considering this standpoint, academics fail to acknowledge how the factors of racism, epidemics, and capitalism have essentially worked together to ensure the delegitimization of Jews not only in the medical field, but in the Americas as a whole. Despite the valiant efforts and subsequent successes of Jewish medics during these epidemics, as is exemplified in the careers of David Cohen Nassy, Matthias Nassy, and Walter Jonas Judah, antisemitism in the context of pandemics has persisted, ultimately ignoring the influential part Jews have played in confronting disease outbreaks.

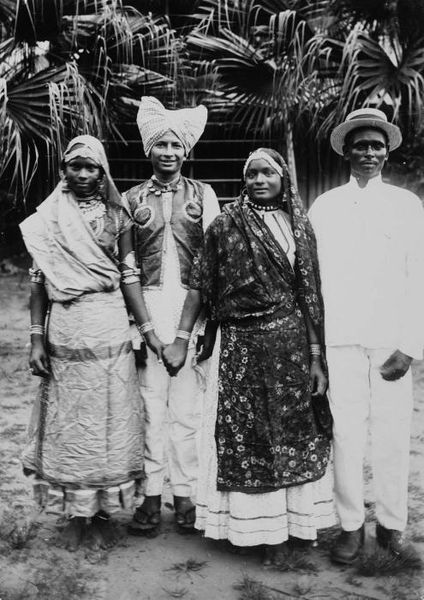

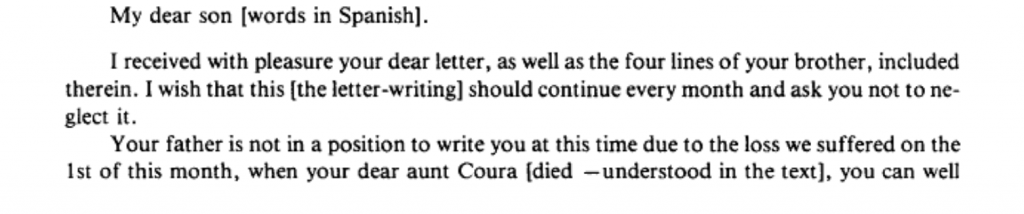

Leibman’s claim is best reflected through her careful analysis of several Jewish healers, David Cohen Nassy, Matthias Nassy, and Walter Jonas Judah, active helpers in the midst of the United States yellow fever epidemics during the late eighteenth century. Much of her argument is detailed through the lens of early scientific racism, which “both enabled and marred the Jewish experience of the Enlightenment” depending on one’s race and ethnicity (Leibman, 79). This was a key factor in discrediting Jews for their work within the medical community, often using their statuses as Jews of color to downplay their role in combating yellow fever. David Cohen Nassy, a Portuguese Jew from Suriname, had incredible success when treating patients for yellow fever and even published extensive research on yellow fever; however, American academics failed to acknowledge Nassy’s efforts and rather fixated on the “low number of Jewish deaths” from yellow fever, a fact that was ruminated on by non-Jews with an air of suspicion (81). Surinamese immigrant and former slave Matthias Nassy, who worked as a nurse alongside David Cohen Nassy, was similarly discredited, not only on the basis of religion, but because he had African ancestry. Even after being freed through the Emancipation Act of 1780, Matthias’s service was “undercut” by various academics and publishers. This includes publisher Matthew Carey, who only mentioned Matthias’s work in his publications to criticize the labor of non-white nurses, the rates Black workers charged for joining hospital staff or assisting with burials, etc. Jewish erasure within the medical field is further exemplified by the fact that the efforts of these men are hard to track within history; David Cohen Nassy was able to maintain a legacy through self promotion, however, our understanding of Matthias’s life remains vague. All of these examples relating to non-Jewish reception of established Jewish figures speaks to the antisemitism present in the eighteenth century, which illustrated Jews not as benevolent and altruistic, but rather as sneaky, conniving outsiders not worthy of integrating into early American society.

Being that this article appeared to me to have many great strengths, I would like to begin by touching on some minor weaknesses. While I enjoyed reading about the life of Walter Jonas Judah, whose life was “shaped” by yellow fever, I thought his story diverged slightly from those of David and Matthias, who were more directly involved in the medical field (83). I was also prompted to wonder as to if Judah’s death could almost be considered something that would break down antisemitic stereotypes in relation to health crises, as the general American public appeared to be so suspicious of how many Jews were unaffected by yellow fever.

One strength of Leibman’s article lies in her ability to clearly and concisely lay out the stories of three very different Jewish men from a similar time period. With an already gripping argument about the impact of pandemics on the Jewish community, the rich analysis of the Nassy men and Judah further strengthened Leibman’s claim while also giving an in depth insight into Jewish life in the Americas during the eighteenth century. With Leibman so carefully crafting the timeline in which these events took place and effectively contrasting the public’s perception of Jewish healers versus the realities of their respective situations, it was incredibly easy to be convinced by her argument. Something I also perceived as being very strong in Leibman’s essay was the way in which she articulated her thoughts, which made the material more accessible to me as a young college student who is not totally familiar with the grave impact that epidemics had on the Jewish community. The fact that this topic is also so closely related to events that we are experiencing day to day with the presence of the coronavirus also helped to keep me engaged with the material and curious to figure out what stereotypes we are still being used today.

Despite the attempts of antisemites to discredit Jews for their contributions to fighting against epidemics throughout history, Laura Arnold Leibman’s article directly denounces the myth of Jewish self interest altogether. Instead, we are made to understand the constant charity, altruism, and work that Jews put into their communities on a daily basis. Perhaps they did not receive the recognition that they deserved for their efforts in the eighteenth century Americas, but we can work to celebrate the progress they made in present time.

Works Cited

Leibman, Laura Arnold. “Jewish Healers and Yellow Fever in the Eighteenth-Century Americas.” Jewish Social Studies, vol. 26 no. 1, 2020, p. 77-90. Project MUSE muse.jhu.edu/article/ 774653.