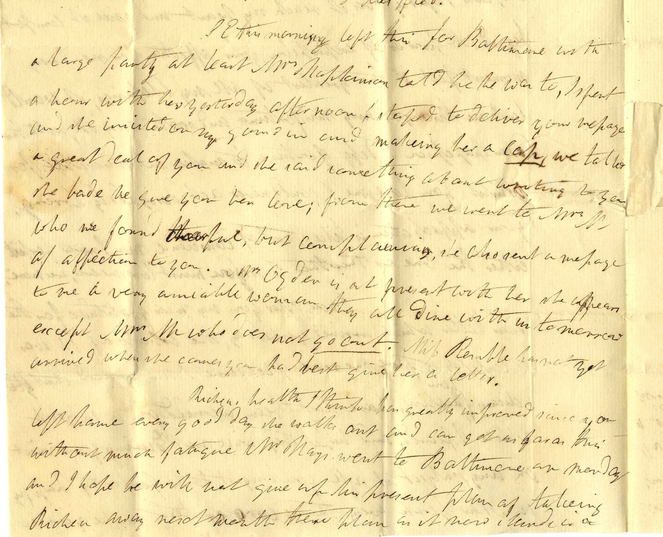

This is an excerpt from a letter written in1944 from Rabbi Bamberger, a practitioner of Reform Judaism, to Allen Bernstein, a congregant. In the letter, Bamberger responds to Bernstein’s recent ‘less-than-honorable’ discharge from the military as a result of homosexual behavior. Bamberger and Bernstein’s open discussion of homosexual feelings is rare for the time period. Note how Bamberger’s language reflects both harmful ideas about homosexuality but also a sense of tough love for Bernstein and concern for his future.

Sources: Noam Sienna (University of Minnesota), “A Rabbi counsels a Gay Jewish G.I” (New York, 1944)

Snitow, Edited Ann, Christine Stansell, and Sharon Thompson. “The Politics of Sexuality,” n.d., 7.

Cuordileone, K A, “Politics in an Age of Anxiety”: Cold War Political Culture and the Crisis in American Masculinity 1949-60″, The Journal of American History; Sep 1, 2000; 87, 2; Periodicals Index Online pg. 515