Hey y’all! Feel free to check out my exhibit. Art steps was not my friend the past 48 hours so I’m sorry if transitions aren’t very smooth… (let’s just say I had to use 3 different laptops on loop because they all kept overheating lol). Much love to you all and it has been so great to be in this class <3

Author Archives: jeweiss

PRECIS 2: Studying Jews of Color in North America

The common ground here is that the race of Jews is defined by hegemony culture. And since those who colonized the Americas came from Christendom, that is Europe, the predominant culture was thought of as white. Therefore, since Jews who colonized the Americas were not black, they were defined by their whiteness. However, in actuality, there are Jews of different races throughout the world since Judaism was proselytized until Constantine, and was spread as a religion by traveling merchants. It was brought to enslaved persons and other people of color in the Americas as well.

In reality, Jews have never been only white. This matters because Jews of color are not counted when considering Jewish demographics, they are not usually talked about nor included when discussing Jews and Jewish history in general, and they are not actively welcomed into the larger Jewish community. Gordon argues that in order to learn Jewish history and study Jews, it is essential that we must learn about Jews of color and make an effort to bring them into mainstream contemporary Jewish life.

One of the strengths of Gordon’s article is his argument that Jews exist across the globe: instead of going out to see in which communities you might find Jews, go to any community and you will (likely) find a Jewish population within it. I also found Gordon’s personal relationship to the topic of the article to be a strength. He leverages his own identity as an Afro-Jew within the article. In particular, he shares his decision to name the department at Temple University the Afro-Jewish Studies Department in order to spark interest in the type of diversity he is referring to (as opposed to socio-economic or Sephardi/Ashkenazi). He explains to those who seek clarification that the studies relate to those like him who identify as both African AND Jewish, as opposed to the assumed focus on the relationship between African Americans and Jews.)

While I agree with the author, it seems to me there might be a hole in his argument in the second to last paragraph of this article. Gordon argues that halakhically some descendents of enslaved people are Jewish, which I don’t think would make sense (only halakhically speaking) if they are descendents of a Jewish father/slave owner (unless Jewish women were being impregnated by non Jewish black men, which I assume was rarely the case). If what he meant was that the enslaved persons were Jewish because they identified with their owners, or because they were the descendents of Jewish fathers, that would not be halakhic (based on traditional Jewish belief in matriarchal descent). I also feel that the article would have been stronger had Gordon provided more hard evidence. While Gordon does a great job using anecdotal evidence, there aren’t very many statistics or actual research results presented to verify his claims. Of course, it is one of Gordon’s contentions that researchers have ignored collecting demographic data from Jews of color, so that might be why. However, without even some very rudimentary statistics, it might feel like Gordon’s assertions are not as significant as he claims.

The Jews of Bridgetown, Barbados Exhibit Brief

Here is my Exhibit Brief

Ottoman Jews and Plagues

In Yaron Ayalon’s article on Jews in the ottoman empire, it is explained that there is a common narrative in the world of Jewish history that during times of plague the Jewish minority tends to be blamed and suffer more from antisemitic acts at the hands of the majority culture. In Ottoman Jews and Plagues, Yaron Ayalon attempts to show that contrary to the narrative that Jews were always the target of blame during pandemics and plagues, the antisemitic pattern was not particularly prevalent in the Ottoman empire. Beginning by looking closely at the Jewish community in Aleppo, the author finds that the central government was limited in the types of support that they provided communities, primarily tax remissions, routing of grain shipments between different areas and basic infrastructure support – such as the rehabilitation of public structures after natural disasters. Otherwise, communities relied on their own religious based organizations for support. In typical times, Jews were well integrated in society and there were a limited number of wealthy Jews who supported Jewish communal structures. During times of disaster, those wealthier individuals tended to limit their support once the need became overwhelming, and flee the area. Others in the community tended to remain. However, this tendency was not exclusive to wealthy Jews, but to the wealthy classes in general in the Ottoman empire. It appears that the tendency towards antisemitic responses to pandemics seen in Europe was not evident in the early Ottoman empire and therefore cannot be generalized outside of Europe. The narrative of Jewish persecution as a consistent theme of the Jewish people does not appear to be a universal narrative.

A couple of aspects of Ayalon’s piece that I appreciate in terms of his content are some of his methods to disprove unfounded antisemetic accusations. One method within his argument that felt persuasive was including information regarding the influence of socioeconomic status at the time. I also appreciated when he included the comparison of how Jewish communities handled pandemics to non-Jewish communities, and how there was very little variance. In terms of how Ayalon structured his essay, I feel it was wise including a question at the end of the article to help clearly answer the “so what” aspect of this piece. However, I also feel that Ayalon made a lot of generalizations in his article rather than make his arguments based on evidence more clearly to the reader. I feel that Ayalon sometimes shied away from going more in depth on some of his points, for instance discussing the interconnectivity between Jewish communities in the Ottoman empire. I also feel that it was a missed opportunity not to bring up comparisons of antisemetic attitudes regarding Jews and pandemics in Europe to those in the Ottoman Empire to get a better grasp on the topic.

Portrait of Abraham Rodriguez Brandon

The image above is an oil canvas portrait of Abraham Rodrigeuz Brandon, a Barbadian born Jew. Brandon was very involved in the Nidhe Israel congregation in Bridgetown, Barbados and was the parnas (financier) for the congregation. Brandon’s full sized portrait is representative of his elite status in society. The clothes he bears are clearly very fine clothes which help highlight and elevate his status. The beautiful nature background as well seems to intentionally imply a high level of wealth since it requires much more detail and time than a plain backdrop. The fact that this portrait was painted by John Welsey Jarvis, a very famous painter at the time, goes to show that immense level of riches and prestige Brandon had (due to his involvement in sugar trade).

Poem from the perspective of Rebecca Valverde Gomes

To be a woman: is to only know the word of men?

by Jesse Weiss

My heart no longer misguided

Rains down, my image withers

Born of choice only

Men hold

I grasped in my fingers

A fleeting moment

Hashem broke the mold

When they made me

Indecent

Douse me in rouge

But let my child

Be among

Chosen Men

So that his cage does not

set.

The Rebellion of Rebecca Valverde Gomes

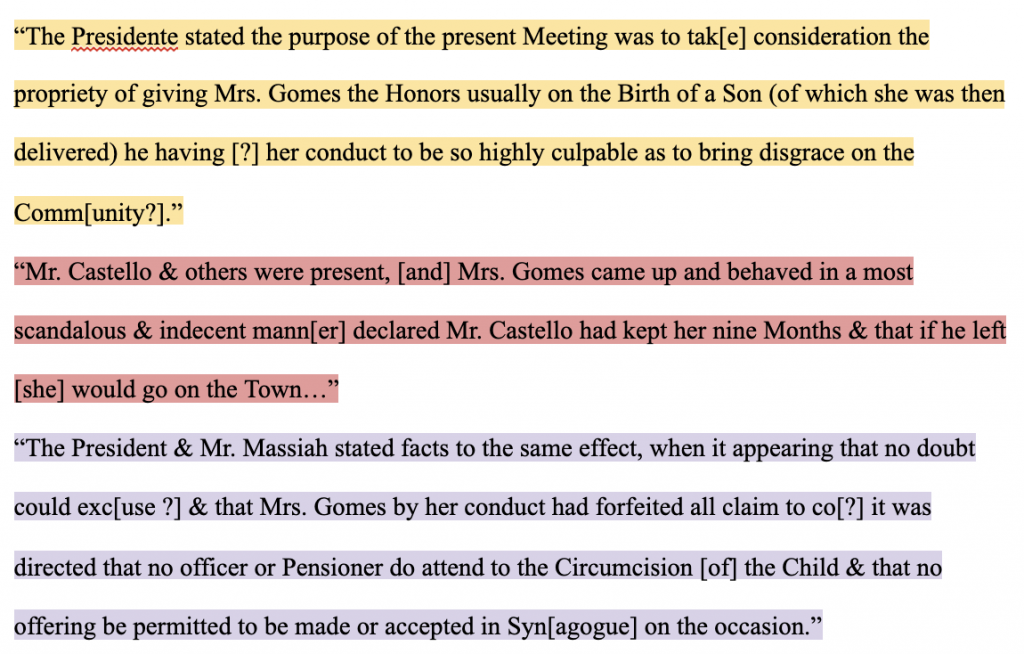

The quotes above come from records of the Mahamad discussing the circumcision of the son of Rebecca Gomes. Rebecca Valverde Gomes was a woman who took part in a massive scandal in the Nidhe Israel Congregation in Bridgetown Barbados. Mrs. Gomes, while married (however left her husband), lived and had an affair with another man . While pleading with the synagogue to circumcise her son, the meeting showed her little mercy (although perhaps more so than other women in her position). In the quotes above lies the apparent rejection of Mrs. Gomes’s appeal with testimony as evidence of her character (shown in the second quote) which was referred to in the minutes as “fact.” This testimony painted Mrs. Gomes as an “indecent” and “scandalous” individual, going so far as to imply that Mrs. Gomes threatened more reckless behavior if Mr. Costello (her lover) would leave her. The board used this as testimony as proof that she forfeited the right to have her son circumcised. This record seems to be a reflection of the way women were viewed in the eyes of the Synagogue, worth mentioning in scandal and viewed with little to no compassion.

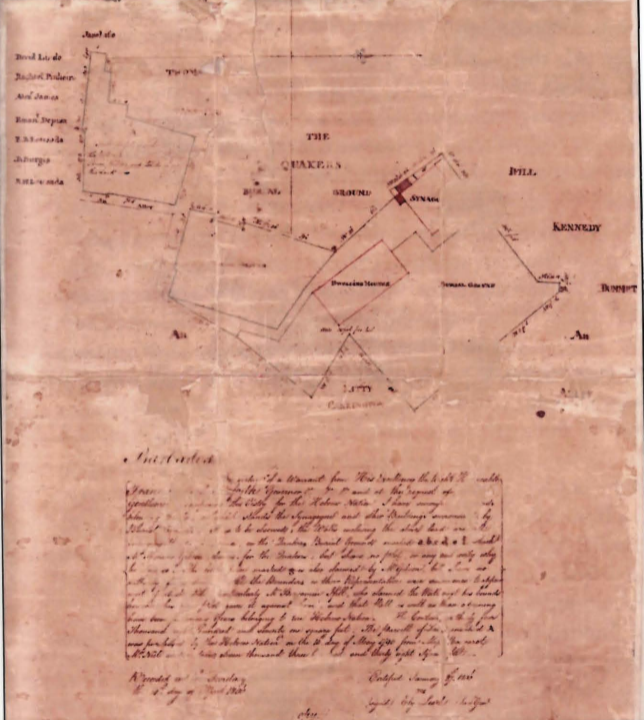

Nidhe Israel Synagogue: Mikveh vs. Cemetery

The Nidhe Israel Synagogue located in Bridgetown, Barbados is home to a historic synagogue layout/complex much like others in the Atlantic World, including a synagogue sanctuary, staff housing, school, cemetery (unlike most complexes), and mikveh. Unfortunately, Nidhe Israel went under the process of rebuilding several times due to hurricanes in both 1780 and 1831. Although, the plat of the synagogue grounds c.1806 shows that the current structure precisely follows that of the one that stood in 1654. The Nidhe Israel mikveh, which was at one point built over after one of the natural disasters but then later found and preserved, is the oldest mikveh in the americas. The mikveh was used as a traditional spiritual bath for jewish women who would cleanse themselves after menstruation and childbirth as well as following conversion. However, at one point the keeper of the mikveh allowed women who were not Jewish but involved with jewish men to cleanse themselves, which when eventually caught resulted in great disapproval and the firing of the mikveh keeper. I found this especially interesting considering the fact that non jewish women using the mikveh seems like it could violate the spiritual sanctity in a similar reasoning to having a cemetery on the same grounds as the mikveh. I can understand why there were so many parts to this synagogue complex considering it was the primary Jewish center for the island. However, it is very unusual to have a spiritual bath and cemetery on the same grounds because mikvehs are used to ritually cleanse impurity, while cemeteries are considered places riddled with impurity, so much so that many jewish cemeteries have a water feature so people may cleanse themselves of any impurity as they leave. To my understanding, the juxtaposition of the two could be understood in both advantage and disadvantage. The advantage: having a mikveh close to the cemetery could be seen as an easy means of spiritual cleansing to balance out any unholiness that is associated with the dead. Disadvantage: Referencing to what I implied earlier, having the association of death so close to not only a holy place of worship like a synagogue, but also a mikveh creates a tainted spiritual environment that does not allow the purity/holy aspect (a very important aspect) exist in the jewish community on this island.

Sources:

Nidhe Israel Synagogue Complex & Mikveh (Barbados, 1654-present). Karl Watson, “1806 Plat of the Nidhe Israel Synagogue in Bridgetown, Barbados,” Journal of the Barbados Museum and Historical Society, Vol. LXI, 2010.

Pioneers of Pauroma: A Jewish Travel Narrative

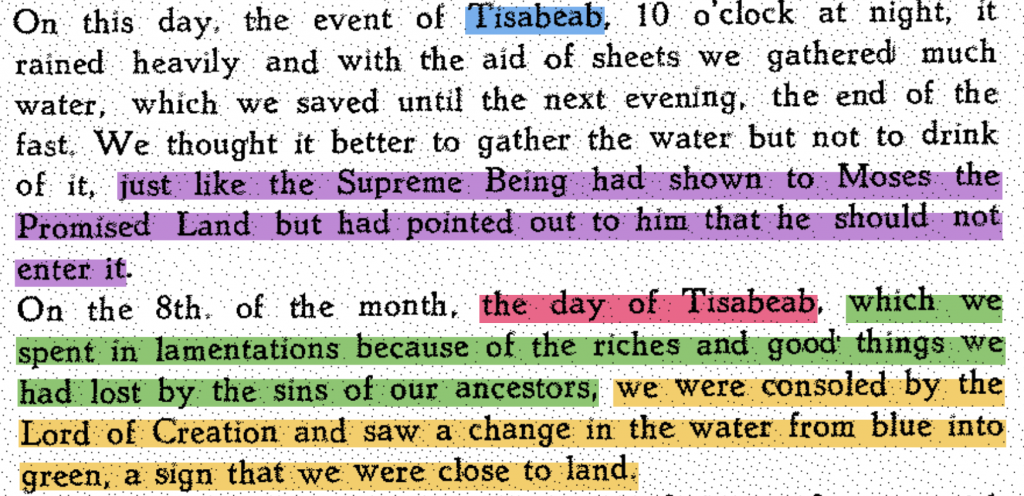

The following excerpt is from Pioneers of Pauroma. It is an excerpt from the retelling of a journey made by Jews from Middelburg traveling to a beach located on the Wild Coast.

In this text, the author mentions that while on their journey the jewish travelers observed what they reference as “the event of Tisabeab”. Tisabeab, or better known in hebrew as ט׳ באב/Tisha b’Av, is the 9th of the month of Av in the Jewish calendar. As to explain why the voyagers did wait until the following evening to drink the water they collected, this is a date that is observed by Jews as a day of fast, commemorating/mourning the destruction of both the First and Second Temple. Like all days and holidays in Judaism, the observing begins on an evening and ends on either the following evening (or the evening of however long that holiday/date is traditionally observed). The author also references that they did not drink the water on Tisabeab because they compared their situation to a story about Moses. I believe this reference has a sort of double entendre, first comparing the Jewish travelers to Moses, therefore comparing the Americas to the Promised Land and implying its great level of significance to them. The other interesting part of this reference is that Moses was led to Israel but could not enter it because of a dispute with God about providing water to the Israelites, further highlighting the water play/aspect of this scenario for the travelers and using the reasoning that they do not want to repeat the mistake Moses made so they can enter their new promised land (Carribean/South American coast). This travel-author’s references and language further suggests the influence and extent that their religious faith had on their journey and its personal meaning to the concept of finding their promised land/home.