This is a section from a 1944 letter written by rabbi Bernard J. Bamberger to his congregant, Allen Bernstein. The letter reveals that Bernstein was discharged from the United States Army for his homosexual identity. A closer reading of the letter reveals Bamberger’s tone expresses genuine concern for Bernstein’s well-being while also showing a personal battle with his developing ideas concerning homosexual relationships through his friendship with Bernstein.

Author Archives: varahs

Précis on Black Judaism in Harlem

James E. Landing’s chapter, “Black Judaism in Harlem, New York City, 1896-1930,” gives a brief history of the establishment of black Judaism in New York. In the late-1890s through the early-1900s, evidence of black jews and Jewish families began to appear, and black preachers, such as Prophet Crowdy, took to the streets of Harlem to spread the word of Judaism. Landing continues to describe the establishment of foundations such as the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA), the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), and the movement sparked by Warien Roberson, an evangelist, who began what became known as “Roberson’s movement.” Roberson’s followers were taught the doctrine, “we who are black worship Christ; Christ was a Jew; therefore we are Black Jews” (Landing 122). The chapter goes on to mention several other influential black rabbis such as Arnold Josiah Ford, Wentworth Arthur Matthew, and Mordecai Herman and their impact on the black Jewish community in New York City and elsewhere.

One strength of the chapter is Landing’s use of a summary at the end of the section. He covers a lot of dense factual information throughout the chapter, and the addition of a summary effectively consolidated the chapter in an accessible page and a half long section. Another strength featured in Landing’s piece is describing the important interconnections between each rabbi mentioned in the article. This highlights the universal efforts it took to create congregations, gather followers, and come together to fight oppression in other countries. While Landing effectively examined many influential participants of the black Jewish movement that began in New York City in the early-1900s, the formatting of the chapter was arguably disjointed, and the amount of detail placed on each rabbi is unequal. Another weakness of Landing’s chapter is that it is challenging to parse what his exact argument is until the conclusion of the chapter. In the main sections, he describes the life and work of each black rabbi and mentions their connection with one another but does not detail a tangible thesis. After the chapter concludes, readers then understand the Landing’s purpose is to emphasize the various strategies for black rabbis in New York City to popularize and spread Judaism.

Landing, James E., Black Judaism in Harlem, New York City, 1896-1930, Black Judaism: story of an American movement, Carolina Academic Press, (2002): pp. 119-157.

Rabbi Arnold Josiah Ford

Précis: Lessons of Hurricane Katrina for American Jews

In the article “Lessons of Hurricane Katrina for American Jews,” Karla Goldman explores the impact and destruction of Hurricane Katrina on the New Orleans community and the Jewish community’s response to the storm. She incorporates the current Covid-19 pandemic and describes the disaster response strategies to Katrina and applicable lessons gathered from the 2005 hurricane to the pandemic. One overarching similarity that Goldman mentions between the two crises is the disproportionate effects on the African American and other minority communities due to a lack of access to health care and public safety. Ultimately, she criticizes the American federal and state government’s continued inability to respond effectively to times of crisis, yet displays how through coming together in times of need, the Jewish community can develop its independent disaster response to assist those in their local communities.

Goldman’s argument is strengthened by her use of listing the valuable lessons learned from the response to Hurricane Katrina and their application to the COVID-19 pandemic. She writes, “History matters…Do not dismiss mainstream Jewish institutions…We are in this together…Put on your mask first…Money isn’t everything” (186-187). Another strength of the article’s argument is Goldman’s overview of the specific successful responses to the Katrina crisis, especially those directed by the Jewish community. These included a systematic effort from the Jewish community, fundraising, mental health services, and food assistance. All of these efforts can be extended and applied to the Covid-19 crisis. Goldman mentions Jewish oral histories collected from Katrina. I believe that something that could have been included to strengthen her argument is the oral histories of Jewish survivors of both Hurricane Katrina and those experiencing the Covid-19 pandemic. A first-hand account of both tragic experiences may strengthen the argument and provide additional insight into the response of the Jewish community and its impact on it. Goldman writes, “As with COVID-19, however, the most devastating impact of Katrina was felt by the city’s poorest, mainly African-American, residents, while people with more resources and white skin privilege were better prepared to navigate the crisis” (184). She highlights that communities of color are more heavily affected in times of crisis like Covid-19 and Hurricane Katrina. However, Goldman fails to pose potential solutions to this problem. While she surfaces effective response strategies implemented during Katrina, they are not targeted to the African American community. She additionally admits that the United States federal and state government have not made much progress in disaster response since Katrina. Rather than proposing solutions, she merely exhibits hope that Covid-19 will result in positive change for the African American and other minority communities.

Goldman, Karla. “Lessons of Hurricane Katrina for American Jews, 2020 Edition.” Jewish Social Studies vol 26, no. 1 (2020): 181.

Isaac and Sophia Phillips of New York

These photographs of Isaac Phillips and his wife, Sophia Phillips, are daguerreotypes that replaced silhouettes as a less expensive portrait. The shift to using daguerreotypes is arguably related to increased antisemitism in the mid-1800s. Earlier silhouettes featured the subject’s profile view, whereas daguerreotypes show the sitter facing forward or angled slightly. Due to these side profiles resulting in antisemitic caricature in the early 1800s, one appeal of adopting daguerrotypes was to convey a representation of the subject that limited the display of Semitic features and potential racist response. In the images, Isaac is pictured with a slight smile on his face, well-dressed, and a book at his side. Sophia’s facial expression differs noticeably from her husband’s as she looks forward with a straight face on the verge of a frown. Her hair is covered by a bonnet and is also dressed nicely. Neither subject wears any accessories, and their posture is relaxed, resting their arms on a side table while sitting upright. Considering the single print of daguerreotypes and a somewhat laborious process to make them, it is likely that the Phillips took the photographs for personal use to document their family history.

Pierre’s Response to Rachel’s Letter

My dear mother,

I am grateful to hear from you, and I am pleased that you received my last letter. I heard from my brother, and he is in good health. I plan on sending him the estate products shortly. I enjoy practicing my penmanship and keeping in communication with my cherished family and will not forget to write.

I, like my father, continue to mourn the loss of my aunt Coura and wish that he writes soon once his grief eases.

I am, with all the tenderness and sincerity I am capable of, your son,

Pierre

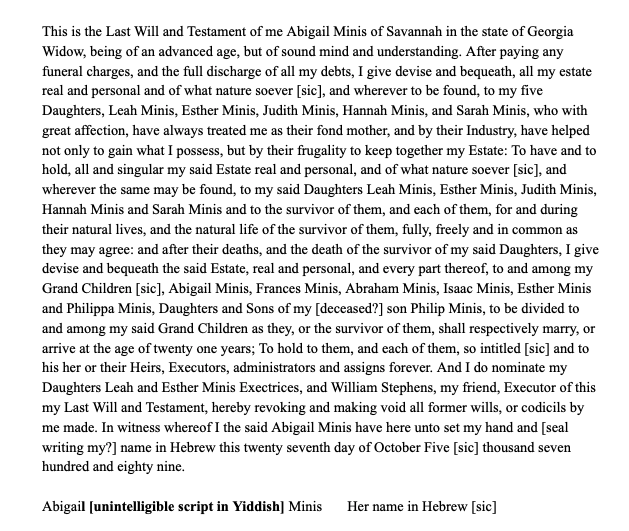

Abigail Minis’ Last Will and Testament (1794)

Pictured above is the will of Abigail Minis (1701-1794), one of forty-two settlers who traveled from London, England, to Savannah, Georgia in July of 1733. After her husband bequeathed his estate to Abigail, she collected large amounts of property, land, and slaves. Her will represents the ability of colonial widows to thrive without the support of male family members. Lastly, Abigail’s legacy highlights colonial women’s ability to experience significant economic growth through acquiring property in the form of land and slaves.

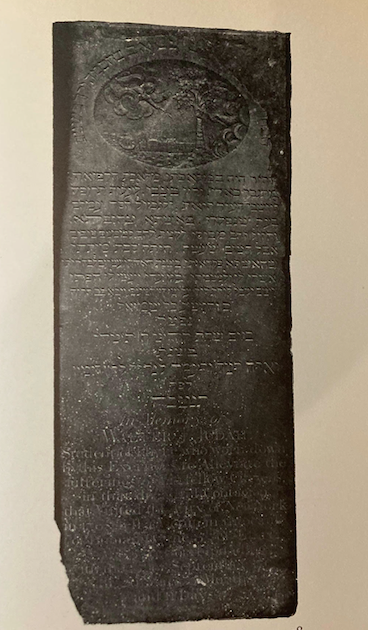

Gravestone of Walter Jonas Judah

Dr. Walter Jonah Judah was one of the first Jewish people to enroll in a New York state medical school. He attended King’s College, which is now Columbia University, from 1794 to 1798. Throughout the mid to late 1790s, the deadly yellow fever epidemic devastated the east coast. Judah, despite not yet completed medical school, joined the efforts to help those who fell ill. Unfortunately, he died in New York City, NY, at age 20 from “that which he had sought to assuage.”

He is buried in the First Shearith Israel Graveyard, also known as the Chatham Square Cemetery. It is located in Lower Manhattan in the Chinatown district and is the oldest remaining Jewish cemetery in New York City. Along with Walter Judah, Revolutionary War veterans are also buried there, and an annual Memorial Day celebration is held at the burial ground.

Sources:

“America’s First Jewish Congregation.” Congregation Shearith Israel, Chatham Square Cemetery.

Cohen, Theodore. “Walter Jonas Judah and New York’s 1798 Yellow Fever Epidemic.” American Jewish Archives, 1996.

French, Mary. “First Shearith Israel Cemetery.” New York City Cemetery Project, 1 Dec. 2010.

Pool, David De Sola. Portraits Etched in Stone; Early Jewish Settlers, 1682-1831. New York: Columbia University Press, 1953.