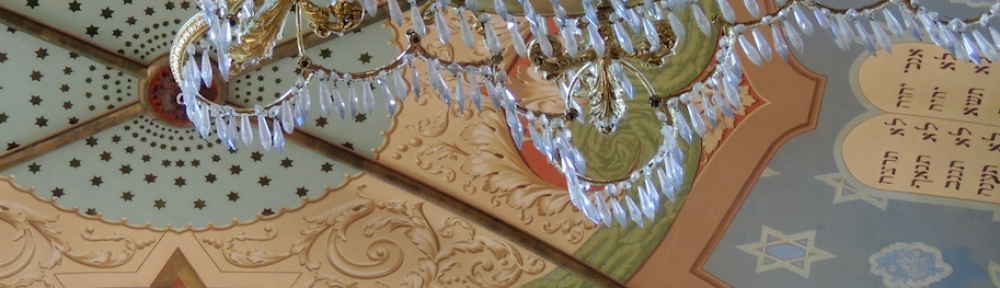

In the chapter “Introduction: Crossing Disciplines, Cultures, Geographies” from Sarah Phillips Casteel and Heidi Kaufman’s greater text Caribbean Jewish Crossings, Casteel and Kaufman highlight the misconception that many academics have regarding the distinction and perceived separateness of Jewish and Caribbean cultures, oftentimes resulting in the erasure of the Jewish-Caribbean perspective in academic texts. However, with the historical presence of the Jewish community throughout the Caribbean colonial world from the start of the seventeenth century as well as “the weaving together [of] African and Jewish narratives,” Casteel and Kaufman suggest that there are deeper historical and cultural ties between the Caribbean and Judaism (Casteel and Kaufman 2). The significance of this chapter lies in its ability to draw attention to a culture that has been largely ignored within Caribbean and Jewish studies, ultimately allowing for room where further intersection of these disciplines can take place. Casteel and Kaufman argue that Jewish American literary studies needs to be internationalized as a field in order to best represent the lived experiences of Jews from diverse backgrounds; in doing so, they emphasize the impact of Jewish culture on “narratives of Caribbeanness” (21).

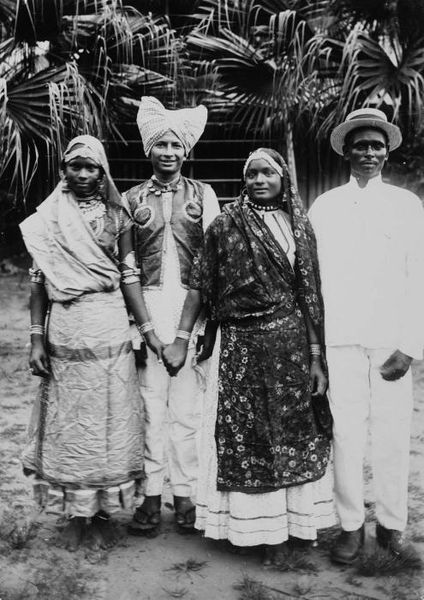

One of the strongest factors of Casteel and Kaufman’s support for their argument lies in their constant highlighting of Jewish historical presence within the Caribbean. In laying out a clear-cut, purely factual timeline illustrating Jewish involvement in the slave trade and plantation customs, it becomes difficult to suggest that intersection between Jewish and Caribbean cultures is impossible. Readers are forced to acknowledge the “historical movement of populations across geographies and oceans” that allowed for the intermingling of of Jews and Caribbeans and the subsequent impact of such a connection on wider Caribbean culture (9). Furthermore, Casteel and Kaufman use this sense of connection and shared diaspora as “one of the fundamental linking concepts that carries across Caribbean literary culture” (10). There is no doubt that Caribbean and Jewish histories diverge from one another, but they share “a common narrative” in their pursuit for a sense of belonging within a world defined so sharply by ideas of colonialism, racism, and divisiveness (22). Casteel and Kaufman further support this argument in their careful analysis of racialization within various Caribbean communities, displaying that an individual’s sense of ‘Jewishness’ remains difficult to define in the face of colonialism and the potential for Jews to be both victims and agents of empire. I also was very appreciative of how Casteel and Kaufman clarified their argument in constantly asserting that Jewish and African diaspora are able to remain distinct and different from one another while still intersecting. They masterfully detailed the complexities of Jewish-Caribbean history while still addressing the nuances of each respective culture.

A weakness I identified while examining “Introduction: Crossing Disciplines, Cultures, Geographies” could be traced to Casteel and Kaufman’s section concerning the essays and samples of creative writing present in Caribbean Jewish Crossings. I was delighted by their prioritization of a “pan-Caribbean approach” when considering the Jewish and Caribbean literary legacy, but the following analysis read less like commentary on the significance of these texts and more of a laundry list of stories and poems that could be found later in Caribbean Jewish Crossings. Rather than dedicating a lengthy portion of this chapter to what was essentially summary of creative writing and essays that were to appear later on in the text, Casteel and Kaufman might’ve found it productive to dwell on the significance of these pieces of literature and their greater influence within the Jewish-Caribbean literary canon.

Despite this shortcoming, Casteel and Kaufman’s chapter manages to give a platform to to Jewish-Caribbean culture, ultimately allowing for greater discussion within Jewish American studies and a better recognition of marginalized communities that have otherwise been ignored in academia. Through the work of academics such as Casteel and Kaufman, we can continue to work towards the internationalization of Jewish studies and better consider the intersectionality of Judaism with wider Caribbean culture.

Works Cited:

Casteel, Sarah Phillips, and Heidi Kaufman, editors. Caribbean Jewish Crossings: Literary History and Creative Practice. University of Virginia Press, 2019. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctvq4bz53. Accessed 31 Mar. 2021.