My students learn early on a few things that really annoy me: imprecise wording and unsupported generalizations. And I labor to give them the analytical toolbox to help them understand politics, but more importantly, develop their critical faculties as citizens.

All this came to my mind when I listened to an interview this morning with Linda Killian, a journalist who has written a book on independent voters, and who I just heard on Here and Now. The book follows a pretty standard script.

Act One: A glib typology that puts new labels on old bottles. Lunchpail Democrats meet Reagan Democrats meet America First Democrats; Rockefeller Republicans meet NPR Republicans; Gen X meet The Facebook Generation. Can you be trying harder to get on the interview circuit?

Act Two: Link a few disparate empirical observations (the “science” portion) with unsupported claims and fill the narrative with anecdotes and quotations from interviews with a few dozen voters. Don’t bother with actual data–that’s far too boring!

The closing act: a series of “reforms” such as the open primary, non-partisan redistricting, and changes to campaign finance. Have we heard this all before?

I quickly pulled over the curb during the radio show. The other drivers probably wondered why I started swerving dangerously! My first reaction was to email John Sides and Lynn Vavreck, whose forthcoming book, The Gamble, will actually show that science, data, and an entertaining take on elections are not a contradiction.

John told me that Ruy Texeira already dismantled Killian’s book in The New Republic in May. No one can stick the fork in quite with the gusto of Ruy:

I SUPPOSE WE should be grateful to Linda Killian. Her new book collects in one place every clichéd and suspect empirical generalization about political independents. So in that sense—and only in that sense—it is a useful volume.

I’ll leave the interested reader to follow up on Texeira’s trenchant observations about Independent voters.

For my students, though, I want to show them how easily with readily available tools you can dismantle what your intuition may tell you is a load of hogwash.

Let’s take just one of Killian’s claims:

Even as the number of voters who consider themselves at the ideological center of American political opinion continues to grow, the number of moderates in both parties in Congress, the ones needed to achieve compromise, shrinks with every passing election, and the political parties become ever more extreme.

This is a significant factor in Americans believing that the country is on the wrong track. Polls show confidence in government is at an all-time low. That feeling is even stronger among the independent voters I spoke with around the country for my new book, The Swing Vote.

Confidence in government is at an all-time low. Independents have lower confidence in government than partisans. It’s nice that she’s so specific. But is she right?

There’s an easy way to find out: the National Election Study and the General Social Survey are available over the Internet. And with a little bit of work, it’s simple to test Killian’s claims.

Claim 1: Confidence in government is at an all-time low. Facts: Trust in government in 2008 equaled the all-time low measured in 1994, but trust in government in 2002 was higher than it had been at any point in the past 30 years except for 1986. On its face, Killian’s claim is true, but the trend over time utterly contradicts her.

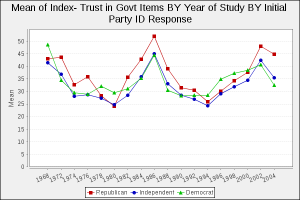

Claim 2: Independents have lower trust in government than partisans. Since Killian refers to “40 percent of all American voters who call themselves independents,” she can only mean Independents before they are asked whether or not they “lean” to one party or another (Texeira explains why this is important). Checking this one out requires a bit more work, because you have to compare different partisan groups, and there are a variety of ways to do this. You can find the table from the NES here, or you can generate the graphic yourself at sda.berkeley.edu (the same online data analysis system can be used to analyze the NES and many other datasets at ICPSR).

Again, the facts aren’t kind to Killian. I don’t know what disgruntled Independents she spoke to, but overall, Independents have not consistently trusted government less than partisans. Shockingly, Republicans rated government best when Republicans held the White House, while Democrats trusted Democratic governments. Independents, it is true, seldom trusted government more than either partisan group, but at only two points over 36 years were Independents both the least trusting and statistically significantly below partisans–1998 and 2000–the same time the two parties were battling over Clinton’s impeachment. Perhaps we can learn something from that period, but I don’t think it has anything to do with the rise of Facebook Friends or Starbucks Moms.

Along with many of my political science colleagues and political observers, I am deeply concerned about our current period of heightened party polarization and government dysfunction. Unfortunately, rehashing theories of independent voters that grew stale a decade ago doesn’t help.

Why Linda Killian gets just about everything wrong

My students learn early on a few things that really annoy me: imprecise wording and unsupported generalizations. And I labor to give them the analytical toolbox to help them understand politics, but more importantly, develop their critical faculties as citizens.

All this came to my mind when I listened to an interview this morning with Linda Killian, a journalist who has written a book on independent voters, and who I just heard on Here and Now. The book follows a pretty standard script.

Act One: A glib typology that puts new labels on old bottles. Lunchpail Democrats meet Reagan Democrats meet America First Democrats; Rockefeller Republicans meet NPR Republicans; Gen X meet The Facebook Generation. Can you be trying harder to get on the interview circuit?

Act Two: Link a few disparate empirical observations (the “science” portion) with unsupported claims and fill the narrative with anecdotes and quotations from interviews with a few dozen voters. Don’t bother with actual data–that’s far too boring!

The closing act: a series of “reforms” such as the open primary, non-partisan redistricting, and changes to campaign finance. Have we heard this all before?

I quickly pulled over the curb during the radio show. The other drivers probably wondered why I started swerving dangerously! My first reaction was to email John Sides and Lynn Vavreck, whose forthcoming book, The Gamble, will actually show that science, data, and an entertaining take on elections are not a contradiction.

John told me that Ruy Texeira already dismantled Killian’s book in The New Republic in May. No one can stick the fork in quite with the gusto of Ruy:

I’ll leave the interested reader to follow up on Texeira’s trenchant observations about Independent voters.

For my students, though, I want to show them how easily with readily available tools you can dismantle what your intuition may tell you is a load of hogwash.

Let’s take just one of Killian’s claims:

Confidence in government is at an all-time low. Independents have lower confidence in government than partisans. It’s nice that she’s so specific. But is she right?

There’s an easy way to find out: the National Election Study and the General Social Survey are available over the Internet. And with a little bit of work, it’s simple to test Killian’s claims.

Claim 1: Confidence in government is at an all-time low. Facts: Trust in government in 2008 equaled the all-time low measured in 1994, but trust in government in 2002 was higher than it had been at any point in the past 30 years except for 1986. On its face, Killian’s claim is true, but the trend over time utterly contradicts her.

Claim 2: Independents have lower trust in government than partisans. Since Killian refers to “40 percent of all American voters who call themselves independents,” she can only mean Independents before they are asked whether or not they “lean” to one party or another (Texeira explains why this is important). Checking this one out requires a bit more work, because you have to compare different partisan groups, and there are a variety of ways to do this. You can find the table from the NES here, or you can generate the graphic yourself at sda.berkeley.edu (the same online data analysis system can be used to analyze the NES and many other datasets at ICPSR).

Again, the facts aren’t kind to Killian. I don’t know what disgruntled Independents she spoke to, but overall, Independents have not consistently trusted government less than partisans. Shockingly, Republicans rated government best when Republicans held the White House, while Democrats trusted Democratic governments. Independents, it is true, seldom trusted government more than either partisan group, but at only two points over 36 years were Independents both the least trusting and statistically significantly below partisans–1998 and 2000–the same time the two parties were battling over Clinton’s impeachment. Perhaps we can learn something from that period, but I don’t think it has anything to do with the rise of Facebook Friends or Starbucks Moms.

Along with many of my political science colleagues and political observers, I am deeply concerned about our current period of heightened party polarization and government dysfunction. Unfortunately, rehashing theories of independent voters that grew stale a decade ago doesn’t help.