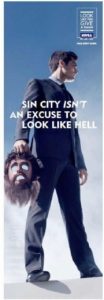

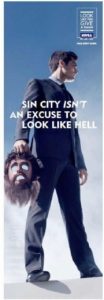

In 2011 Nivea launched their “Look Like You Give a Damn” campaign in the September issue of Esquire, an American men’s lifestyle magazine. The advertisements were geared towards generating a new consumer base to sell their line of ‘Nivea Men’ grooming and skincare products. Assumptions about binary gender roles and identities are immediately apparent in the tagline, which assumes that men in general can’t be bothered with appearances. In contrast to advertisements for ‘female’ products, which stress beauty ideals or luxury, this advertisement assumes the posture of wrangling men into the ‘bare minimum’. Products for the female body are often cast as a means of attracting those of the opposite sex, or as ways of improving inadequate or flawed aspects of their bodies. Here, for men, products identical to those in the women’s line are instead the means to self-realization, professionalism, and status- as depicted in the image below.  Adequate care of the self, ‘giving a damn’, here looks like a clean-shaven face, short hair, and a suit. Gazes directed outwards, and walking towards the viewer, portray confidence and power, while the professional attire inscribes the models within the realm of work and suggests an upper-class position or ideal success. If you don’t use Nivea, or cannot afford to look like this, the ad suggests, you must simply not care enough- and that’s not the right look for the refined, cosmopolitan, capitalist man. To care goes beyond the body, it is to curate the proper subject.

Adequate care of the self, ‘giving a damn’, here looks like a clean-shaven face, short hair, and a suit. Gazes directed outwards, and walking towards the viewer, portray confidence and power, while the professional attire inscribes the models within the realm of work and suggests an upper-class position or ideal success. If you don’t use Nivea, or cannot afford to look like this, the ad suggests, you must simply not care enough- and that’s not the right look for the refined, cosmopolitan, capitalist man. To care goes beyond the body, it is to curate the proper subject.

Other images from the campaign, however, suggest that giving a damn may not look the same or hold similar prospects for all men.

This pair of ads was subject to controversy and eventually led to Nivea retracting the campaign. While the product advertised and the general trope of unmasking are the same between the two ads, the difference in the text is what prompted backlash and was the main target of angry social media users. The slogan “Re-civilize yourself” was only used in this ad, with a black model, and appears in no other images or media in the campaign.

The first image’s text is especially charged in the context of racial politics in the United States. The black man is pictured with his previous, presumably uncivilized, self in his hands, preparing to throw it away. This posture, the tight shirt which emphasizes muscles in the arms, and the angry expression on the head’s face all recall the racial stereotype of the ‘mandingo’ – the oversexed, aggressive, primal by nature, African American male.

What was shed along with this mask was a characteristic afro and beard, attributes of a supposedly ‘uncivilized existence’. Natural hair, in the history of racial prejudice in the United States, has been both a point of contention (battles in the workplace to change black natural hairstyles which are ‘unprofessional’, for instance) and a symbol of black pride and resistance against Eurocentric beauty standards. The Afro is a charged cultural icon which is already involved in contests of ‘civilization’ in a way the second image’s long hair and beard are not. By connecting the destruction/removal of the afro with “re-civilizing”, the ad echoes this long history, and implies that African American culture is itself outside of civilization. The model’s positioning in what appears to be a parking lot, a mark of societal infrastructure, is his return to such a world now that he is sufficiently civil. The frame and the gaze of the viewer are in line with his person. This placement is not ‘exemplary’ in the same way as the elevated second image, it is a banal or everyday location. Unlike the white advertisement, the black model’s use of these products has marked a subtle return to a more basic level of humanity.

In contrast, the variation with the white model suggests a very different social position. To begin with, the subject is placed so that the viewer appears to be looking up at him, where he stands seemingly on the edge of a wall or building in the sky, a god-like position. In contrast to the more casual grey sweater, surely designed to emphasize crafting a less threatening black-body, the white model wears a full suit. The face he holds in his hands is not angry, but nearly comic with a large gaping mouth and eyes similar to the characteristic theater symbol. Additionally, rather than an aggressive posture of throwing the mask, he stands tall and straight, feet spread in a dominant pose, yet his arms are relaxed. He is not threatening, but he is also not threatened- the foot slightly over the edge is enough to signal his daring will.

The caption echoes these differences and reads “Sin City isn’t an excuse to look like hell”. Sin City, Las Vegas, in contrast to the empty parking lot, is a busy and populated locale which symbolizes sexuality, wealth, luxury, and the chance to make it big. This is a sanctioned space in which to ‘let oneself go’, but the ad suggests that on top of this already privileged position in the scene of the city, a man can distinguish himself through his appearance.

To indulge in all that comes with ‘Sin City’ and to still remain distinguished or put together, is to reach the heights that the visual elements emphasize. Being sinful or uncivilized is not what is up for question in this version of the advertisement- advancement is the name of the game. The subject’s position as a white man, already squarely within hegemonic masculinity, allows him to use these products to better himself, and to reach success literally on another level than that of the black model.

This is shown in yet another image from this campaign, where the black model is explicitly excluded from participation in ‘Sin City’. The white males are left to their own devices- looking suave and smug while gambling in dramatic lighting which highlights their jawlines, cheekbones, and dark hair. Again, in contrast to the position of the black model, they seem relaxed and in control of themselves. The use of Nivea’s products, for these men, is not a matter of taming oneself into a civil humanity. Even their longer, slicked back hair contrasts with the severe buzzcut of the black subject- suggesting that some men need to be restrained more than others, or that hair on some bodies is more threatening when left unaltered. At stake in these advertisements are claims to a certain respectable, ideal masculinity, and while Nivea’s products give any man the opportunity to look like he gives a damn, the ads reinforce the hegemony of a white masculinity.