NIVEA is a German beauty product and personal care company that was founded in 1911 to market and sell a new, recently-patented skin cream that demographically targeted white women. The specific benefits of their breakout product, “Eucerin,” were vaguely defined and remain unclear, but the moisturizer gained enough popularity throughout Europe and parts of the United States to allow its proprietors to expand the scopes of their business. NIVEA fully rebranded themselves in 1958, in an attempt to step away from their reputation as simply the vender of their flagship product, and transformed themselves into a larger figure in the skincare industry by introducing various kinds of sunscreen and specialized products for children — while still maintaining a marketing scheme that brazenly appealed to idealized notions of white femininity.

Less than 30 years later, NIVEA further reframed their brand to appeal more widely to the global market that they sought to engage with. And so, in 1986, they sparked a self-proclaimed “Revolution in Skincare” by choosing to encompass men’s skincare needs into their mission statement: “No longer would men have to use products that belonged to their wives, sisters or mothers. Now they could use NIVEA for Men, a range of skincare products just for them.”

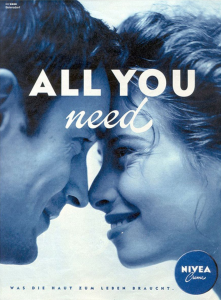

Although this shift in their targeted demographic widened the scope from exclusively appealing to white women to include white men as well, NIVEA’s marketing antics are far from sensitive and accepting — after all, the name “NIVEA” stems from the Latin word “niveus,” which translates to “snow-white.” The two ad campaigns we will be analyzing for our project both revolve around Nivea’s recent perpetuation of and direct appeal to Westernized, white-centered, ethnocentric projections of beauty and health. Up until August of 2011, Nivea’s problematic tendencies were poorly-veiled by a complete lack of engagement with any notion of ethnic inclusivity, which becomes abundantly evident after merely a brief skim through the history of their advertisements: sampled from 1911, 1935, 1964, and 1992, respectively.

But given the heightened awareness to widespread systemic injustice that the 21st century saw, and with a proportionately growing attention paid to the pervasive corporate exclusion of minorities in the beauty industry, NIVEA eventually decided to attempt to venture into the world of intersectionality. Alas, although one of their concluding points in the autobiographical section of their website states “For 100 YEARS we have created skincare products which means NIVEA understands skin like no one else, for any person, male or female and for any skin type – NIVEA for life,” it is ultimately unsurprising that the company’s first few misguided forays into ethnic inclusivity were massive failures, complete with extremely telling cultural implications.