Sarah Haselton

Exploring Cyprus today, one sees English and modern Greek everywhere. That, I’m sure, comes to no surprise to my dear readers, but perhaps you may wonder what script would have been seen a few thousand years ago. If you have not been wondering that, then start now, because I’m going to explain it whether you like it or not.

I must warn my readers now that you may find yourselves crestfallen at the lack of my usual verve and brilliant unending wit in this post, so I extend my deepest apologies. The reason for this is that our fearless leader Tom Landvatter cruelly bullied us for not recalling his singular lesson on Cypriot syllabary in Greek 111, and ever since then I have found myself unable to access my usual character which my readers so deeply love. Indeed it brought me deep shame to not have remembered a lesson from months ago, and I now recognize my absolute failure as a student [n.b. from Tom: this is true, they all should have remembered it]. I only hope the sweat and tears I shed over this blog post, and the many hours of research I committed to it, is enough to redeem myself [n.b. from Tom: perhaps.]. With this apology offered, let’s talk about the Cypriot syllabary, the script used in ancient Cyprus between the eighth and third centuries BCE.

Cypriot syllabary is a descendent of Cypro-Minoan scripts used in the second millennium, which themselves may have evolved from Minoan Linear A. Currently it is unclear whether the script was developed to record an indigenous language or Greek, a problem which is complicated by the lack of understanding of indigenous languages in Cyprus. Evidence from inscriptions show it was used to record Greek and at least one indigenous dialect, Eteocypriot, but the original reason for the script’s development remains unclear.

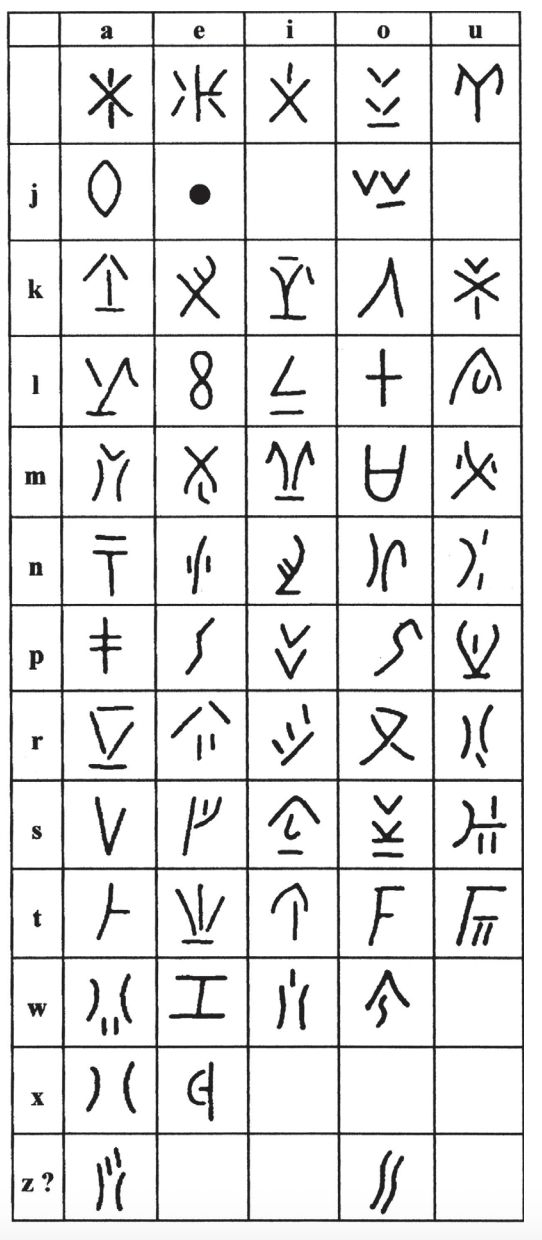

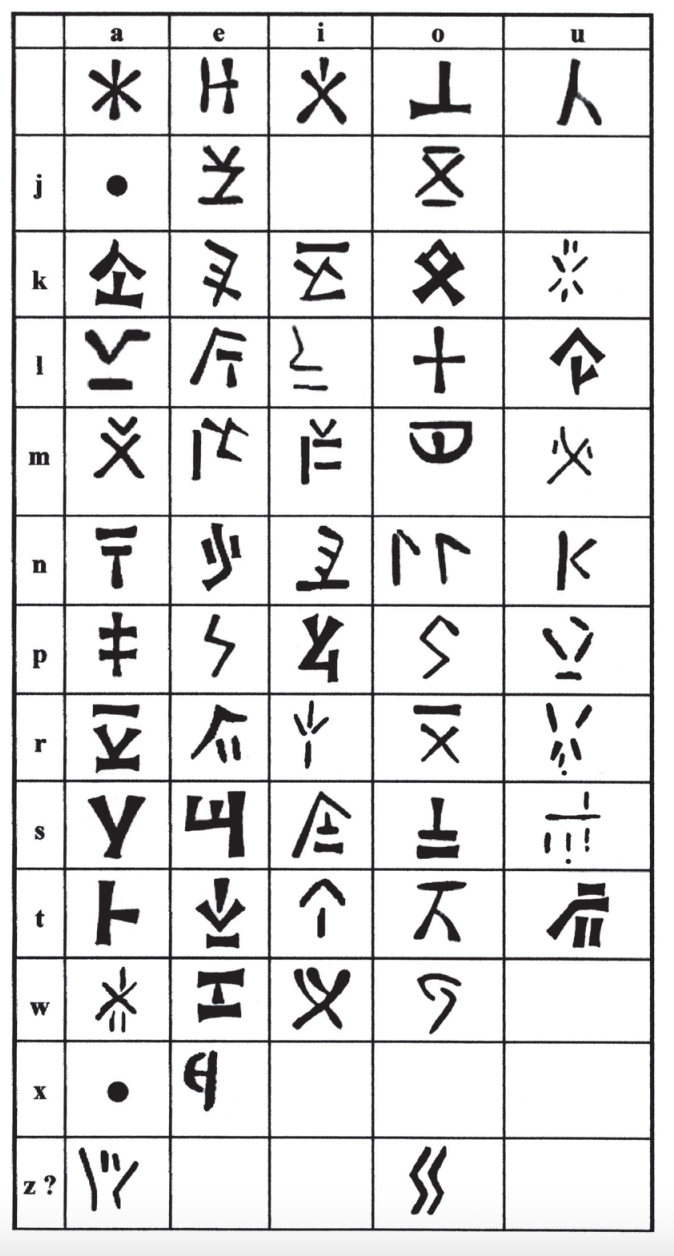

Inscriptions bearing the syllabary are predictably most attested in Cyprus, but can also be found in Egypt, Syro-Palestine, southeastern Anatolia, Greece, and Italy. The script contains fifty-five individual signs:

The script was deciphered in the late 19th century after the discovery of two bilingual Greek/Cypriot inscriptions. Robert Hamilton Lang deciphered the word for king, and along with George Smith and Samuel Birch, cuneiform and Egyptology experts, managed to attribute phonetic values to the script. Several other names come into play, but because I respect your attention span and I’m willing to bet you do not remember the names you just read (because neither do I), I will spare you circumlocution. Don’t worry, I won’t quiz you later [n.b. from Tom: I will.].

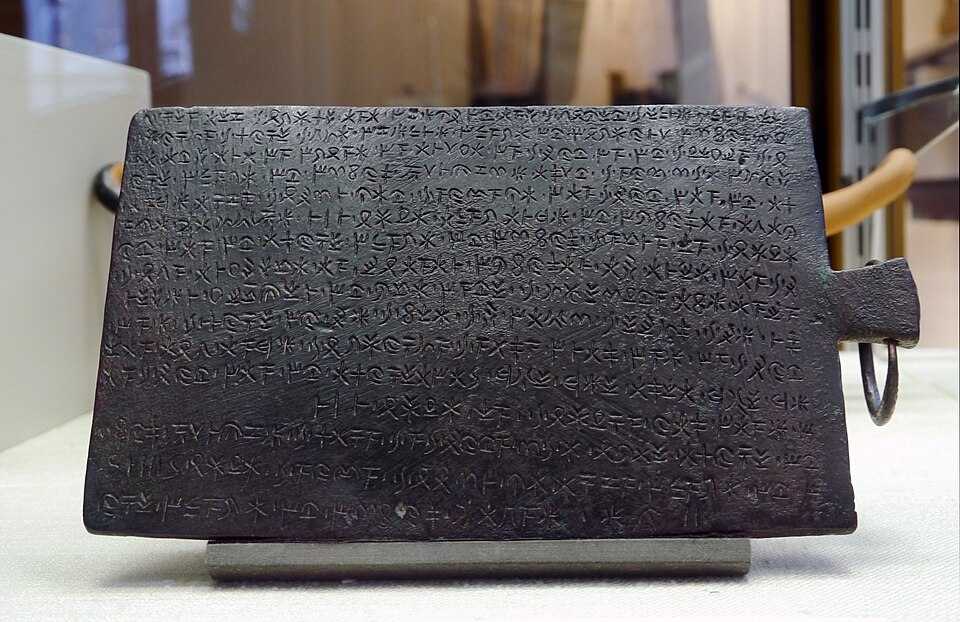

There is an impressive number of extant inscriptions bearing Cypriot syllabary, totaling around 1,400 instances preserved on a variety of objects. Most are funerary or dedicatory inscriptions, but also vases, coins, statues, seals, jewellery, and weaponry. The largest example of the script is the Idalion bronze tablet which details an agreement between the king Idalion Stasikypros and a doctor named Onasilos and his brothers, where the king promised a reward to the family for providing free medical services when the city of Idalion was besieged by the Persians and Kitians (who resided in Larnaca) in the fifth century BCE. One could not imagine that happening today.

There is a second variant of Cypriot syllabary called the Paphian script, with inscriptions coming from Paphos and the surrounding areas. The normal version is attested throughout the rest of Cyprus.

The use of Cypriot syllabary declined in the late 3rd century, with the last attested inscription coming from a sanctuary in central Cyprus from between 225 and 218 BCE. The script’s end is thought to have been as a result of the political and social changes following the death of Alexander the Great. I think I have now spun this yarn as long as I can, though I will include my source below for any avid linguists. I bid farewell to my readers, and, much like the topic of this post, I now shall drop out of existence in this thread. And I do hope that my worth as a student has been recovered, though I suppose that judgment is up to Tom [n.b. from Tom: TBD].

Work Cited:

A. Karnava, 2104. “Cypriot Syllabary.” In Encyclopedia of Ancient Greek Language and Linguistics. Brill, 404-408.