From the 1950s through the 1980s, a steady stream of talented blues and folk artists came through Reed College. With the folk music revival in the ‘50s and the blues revival in the ‘60s, there was no lack of skilled artists across the country. Reed drew in dozens of artists, from smaller local musician Mike Russo to the controversial international sensation Paul Robeson. But what brought so many artists to Reed’s small and considerably unknown campus? It was all due to Reed Cultural Affairs Board– or ‘Reed Cultch’– and Reed Focus Group, two now extinct campus organizations.

One of the early political clubs of Reed, Focus Group, identified itself as a non-partisan educational organization dedicated to bringing forth less-heard leftist views and opinions. For this mission, they invited many blacklisted academics, writers, and singers harmed by McCarthyism to campus to share their stories.1 One such singer was Paul Robeson, who was both a talented bass-baritone blues singer and a controversial political figure.

Robeson was very involved in the civil and human rights movements, but he was also a great supporter of the Soviet Union during the Cold War. Raised under Jim Crow laws in Princeton, New Jersey, Robeson struggled to be acknowledged by his peers and teachers despite his wonderful academics, athleticism, and singing ability. He was accepted into Rutgers University and went on to Columbia University, graduating with a law degree, but no law firms would hire him. Robeson returned to music, bringing his experiences with him. He performed a great deal throughout Europe in the 1930s and while there spent some time in the Soviet Union.2 Robeson found the Soviet Union’s treatment and rights of people of color far superior to the United States and was known to speak highly of the nation.3 He continued to show support for the country even during the peak of McCarthyism, which led to great backlash. Even when the federal courts accused him of being a communist, he did not revoke his support for the nation. This decision, however, cost him his popularity and his right to travel.

Since most other establishments were scared to be associated with him, Robeson had not played a show in nearly 10 years. The opportunity finally arose again when an old acquaintance from Reed, Tommy Bransten, invited him and Focus agreed to sponsor him.1 His invitation to Reed campus sparked quite a bit of discourse among Reedies. He was set to play on March 18, 1958, and up until that day, multiple complaints were posted or mailed regarding his appearance.

One particularly concerned individual directly mailed Reed’s president at the time, Richard Sullivan. The writer, James Lynch, argued that Reed should not be hosting Robeson due to his statements and that the college should not be asking for funding of the people Robeson supposedly wants to eliminate. He believed Robeson should not have a platform at Reed and had quite a bit to say about the ineffectiveness of the system for freedom of speech. Sullivan replied that he had faith in the system and that they had different views on freedom of speech.4

While that mail correspondence was taking place, others took to the Quest to voice their opinions. One student, Peter Rubstein, criticized Robeson and wrote, ”I was first thrilled by the magnetic Robeson, in a performance of Porgy and Bess which spoke eloquently of the character of Robeson, the artist. Yet, in intervening years I have witnessed the transformation of Robeson, the artist, embittered by racial injustices, into the thoroughly unpleasant position of ‘fellow-traveler’. In the eyes of my government, the statements attributed to Paul Robeson, made before foreign audiences, are to be considered inflammatory if not seditious.”5 Yet, only one column away from that review, another student wrote a positive review on Robeson’s autobiography. While the author Mark Ptashne enjoyed the work, he did end his review saying, “If you love Robeson now, you’ll love him as much and perhaps a bit more after reading his book, and if you despise Robeson now you’ll despise him as much and perhaps more after reading his book.”5

Despite objections of some Reedies, Paul Robeson ultimately took to the stage of Botsford Theatre with pianist Miss Jean Sharp and performed a wonderful concert. Though he was barred from sharing his political views, he shared lively songs and poetry to those who attended.

While Robeson was certainly one of the more controversial artists that the group brought in, Focus also continuously invited known communist banjo player Pete Seeger. Though raised in an upper class household, Seeger had always leaned toward Leftism and held sympathies for the working class. His very first music group, the Almanac Singers, was pro-labor and would perform at Communist meetings. Due to his support of the Communist Party and temporary affiliation with it from 1942 to 1949, Seeger was eventually blacklisted from playing at most venues.6 This is what led Focus to reaching out and inviting him to play at Reed.

Seeger’s concerts were held off campus for a time, when Frank Griffin was president of the college. President Griffin believed that hosting a communist would deter Portlanders from funding the school.1 A compromise was eventually reached and Seeger was allowed on campus. Pete Seeger played at the college a handful of times from 1955 through to 1958, enough that one Quest writer remarked that it was becoming a bit of a tradition. One of these yearly concerts was performed with “Blind Sonny” Terry, a talented harmonica player. 7

Starting from the early 1960s, Focus run concerts began to fade, replaced by concerts sponsored by Reed Cultural Affairs Board, or simply “Cultch”. Founded in 1963, Cultch was not so interested in political figures and focused on bringing cultural events to Reed. This led to a great deal of blues and folk artists making their way to campus. One such band was popular blues duo Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee. The charismatic guitar and harmonica duo graced Reed’s campus with their music a handful of times from 1958 up to 1961 and even participated in a campus hosted folk dancing event. The duo allegedly did not like each other very much, and eventually disbanded over a dispute in the late 1960s.8

They were not the only folk artists that couldn’t get enough of Reed, however. Rolf Cahn, a well known folk singer and guitarist, visited campus 4 times over the course of 3 years. Cahn was a member of the Communist party for a short time in the late 1940s, before he was kicked out of the party for teaching martial arts to a police officer.9 Due to his affiliation and his strong opinions, Cahn’s first appearance at Reed on January 17, 1959 was thanks to the Focus Group. He hosted 2 lectures, one on flamenco and one on the musicological aspect of folk music. Cahn also hosted 2 workshops on the theory and practice of folk music and the folk music community in the US.10 The next time he came in May later that year, this time through Reed Cultch, he once again hosted workshops alongside his performances. He visited two more times in 1960 and 1962.

In 1964, Cultch managed to pull in an incredibly influential figure of the folk revival, Reverend Gary Davis. Davis was one of the most renowned East Coast ragtime guitarists in the 1920s and his fame continued until his passing in 1972. He played guitar and harmonica drawing inspirations from both folk and blues music. Davis often preached during his concerts, and he shared stories between songs as well during his Reed concert. Overall it was described as a most satisfactory concert from start to finish.11

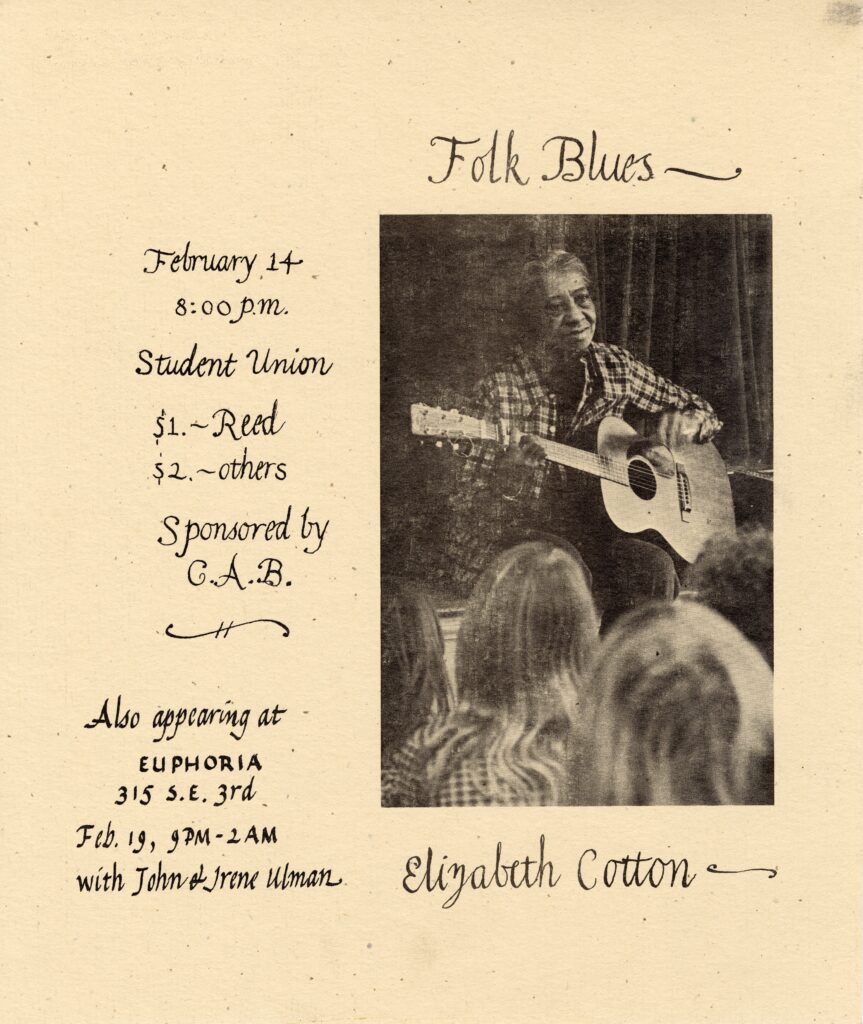

While Rev. Gary Davis was certainly a key figure of the folk revival, Elizabeth Cotten and her music was a staple. Cotten began practicing guitar while still in elementary school and played all throughout her life. Although she released her first album in 1958 at 62 years old, her songs– specifically “Freight Train”– had been circulating among folk musicians for a couple of years.12 She was a wonderfully talented banjo player and guitarist and toured across the country, eventually making her way to Reed College. Through the efforts of former Reedies John Ullman ‘65 and Irene Namkung ‘65 as well as Reed Cultch, Elizabeth Cotten played on Valentine’s Day in 1975. Ullman and Namkung opened for her performance with some folk song covers to warm up the audience. Despite being 82 at the time of the concert, Reedies praised Cotten’s great stage presence and performance.13 Elizabeth died just 5 years after her appearance at Reed.

Cultch kept inviting blues and folk artists to campus all the way through the 1980s. After Cotten’s performance came Queen Yda, the Mick Clark Band, Skip James, Bukka White, Clifton Chenier, Bois Sec Ardoin, Muddy Waters, and even John Lee Hooker. All in all, dozens of talented musicians found themselves at Reed through the efforts of these clubs.

“They Don’t Bite, They’re Just People: Bringing Blues and Folk to Reed,” is on display near the main entrance of Eliot Hall. To listen and learn more about the musicians featured here, please visit the exhibit. Archival recordings of their performances are on display at the exhibit. For additional information, primary sources, and additional recordings from the blues and folk singers visit Reed College Special Collections and Archives Monday-Thursday, 10am-4pm on Lower Level 2 of the library or to email us at archives@reed.edu.

Source List:

[1] Michael Munk ‘56, Oral History.

[2] Colbeck, Cameron. “The Genius of Paul Robeson: As Told by Cameron Colbeck.” Abbey Road, 24 Dec. 2021, www.abbeyroad.com/news/the-genius-of-paul-robeson-as-told-by-abbey-roads-cameron-colbeck-2938.

[3] Robeson, Paul. Here I Stand. Beacon Press, 1958.

[4] James Lynch to Richard Sullivan, March 12, 1958, Box 001, Folder Focus Club 1951, Reed College Student Organization records, Reed College Special Collections and Archives, Reed College.

[5] Reed College Quest, Vol 47 No 21, Mar 17 1958.

[6] Corn, David. “We Obtained Folk Legend Pete Seeger’s FBI File. Here’s What It Reveals.” Mother Jones, 18 Dec. 2015, www.motherjones.com/politics/2015/12/pete-seeger-fbi-file/.

[7] Reed College Quest, Vol 48 No 8, Nov 3 1958.

[8] “Sonny Terry and Brownie McGhee.” All About Blues Music | Life Is Too Short for Boring Music, 22 Aug. 2022, www.allaboutbluesmusic.com/sonny-terry-brownie-mcghee/.

[9] Williams, Alex. “Barbara Dane, Who Fought Injustice through Song, Dies at 97.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 25 Oct. 2024, www.nytimes.com/2024/10/25/arts/music/barbara-dane-dead.html?searchResultPosition=1.

[10] Reed College Quest, Vol 48 No 14, Jan 12 1959.

[11] Reed College Quest, Vol 53 No 19, Feb 24 1964.

[12] McCabe, Allyson. “How Elizabeth Cotten’s Music Fueled the Folk Revival.” NPR, NPR, 29 June 2022, www.npr.org/2022/06/29/1107090873/how-elizabeth-cottens-music-fueled-the-folk-revival.

[13] Reed College Quest, Vol 65 No 2, Feb 7 1975.