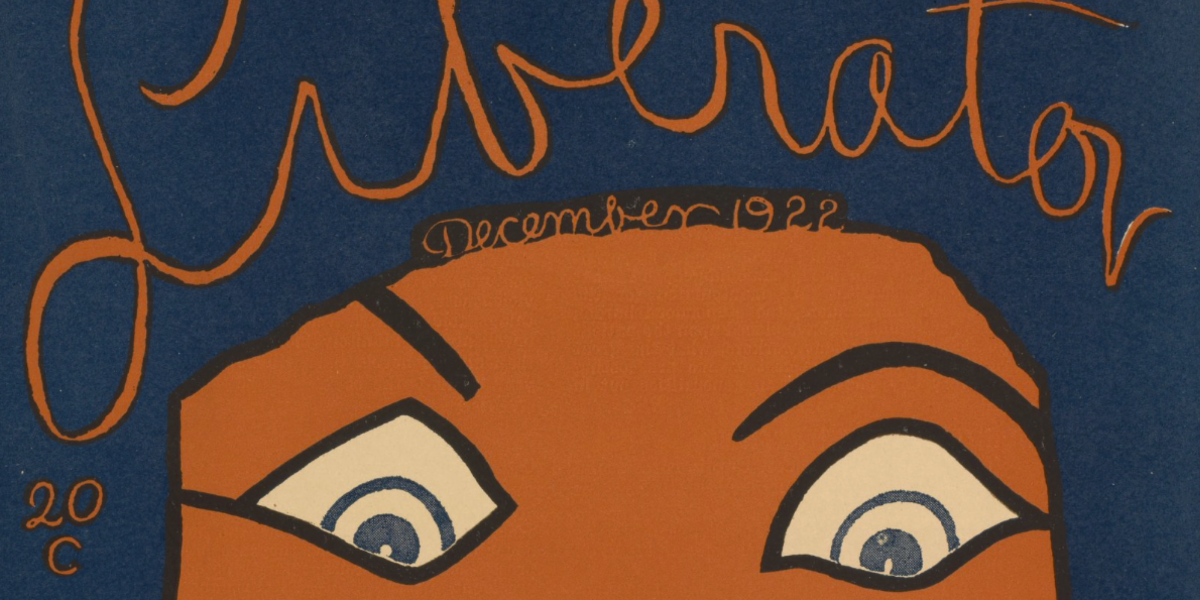

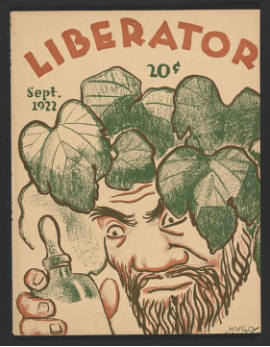

Many have already heard of The Liberator, the 19th-century abolitionist newspaper created by William Lloyd Garrison. However, a new magazine under the same name emerged in the twentieth century. First published in the spring of 1918, the twentieth century Liberator continued the fight for equality: it focused on worker’s rights, women’s rights, and promoted socialism as an alternative to capitalism.

During World War One, the Wilson administration passed the 1917 Espionage Act and the 1918 Sedition Act. The legislation prohibited subversive speech that critiqued the draft, the Constitution, or the United States government.1 Subsequently, the U.S. government shut down socialist political magazine The Masses and prosecuted its editor Max Eastman.2 With the magazine effectively terminated by the U.S. government, Eastman and his sister Crystal founded The Liberator to succeed the defunct Masses.

The Eastmans were an accomplished pair of American activists. Crystal Eastman (b.1881-d.1928) was a labor lawyer, suffragist, socialist, and journalist who worked with her brother (as a co-editor) on the socialist magazine The Liberator. Much of Eastman’s journalistic work focused on the suffrage movement and workers’ rights in the early twentieth century. In 1917, before The Liberator’s creation, Crystal Eastman and other activists established the National Civil Liberties Bureau, which later became the ACLU, to fight government repression of dissenters’ rights during the First World War.3 Eastman is also credited with co-founding the Congressional Union in 1913 (later known as the National Woman’s Party) and supported the Equal Rights Amendment of 1923, a proposed amendment to eliminate federal and state laws that discriminate against women.4

Max Eastman (b.1883-d.1969) was a poet, editor of The Masses and the Liberator, and a prominent socialist and women’s rights activist in the early twentieth century. In 1910 he and other activists founded the Men’s League for Women’s Suffrage.5 Despite his professed belief in men and women’s equality, critics have noted a majority of The Liberator’s articles on women’s issues were written by men. Around 1 January 1922, Eastman passed his editorial position down to literary critic Floyd Dell. Under Dell’s supervision, the magazine’s focus shifted from politics to arts and culture.

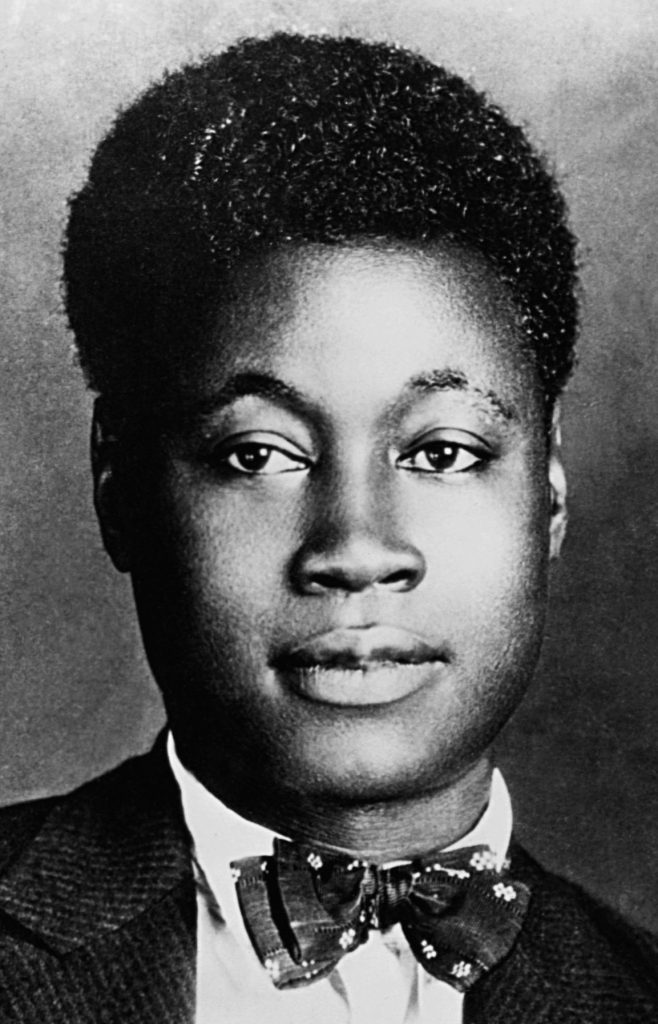

First published in the Spring of 1918, a reader could pick up an issue of the magazine for twenty cents and read about the American labor movement, reports from post-war Europe, and John Reed’s reporting from the USSR. Political art and poetry fleshed out the remainder of the magazine. Contributors included prominent writers such as Claude McKay, a Jamaican-born poet and key figure in the Harlem Renaissance.

Born Festus Claudius Mckay (b.1889-d.1948), McKay was one of the most important poets of the Harlem Renaissance. His work ranged from vernacular verses celebrating Jamaica to poems that protested racial and economic inequality.6

In 1912, using a stipend he earned from the Jamaican Institute of Arts and Sciences, McKay left Jamaica for college in the United States. He attended Tuskegee Institute for two months before transferring to Kansas State College. In 1914 McKay departed college for New York City. His experiences with racism in the United States encouraged him to continue writing poetry.7

In 1919, McKay met and befriended Max Eastman, who later hired McKay as co-editor for The Liberator in 1921: a position McKay would maintain until 1922.8 McKay published several poems in The Liberator, most notably the enthralling poem If We Must Die.9 The poem was first published in the July 1919 issue of The Liberator and republished in several magazines.10 The poem’s publication date is significant as 1919 was one of the most tumultuous years of the twentieth century. There was the Influenza A pandemic, workers unrest, and the Red Summer. If We Must Die was a direct response to news of the race riots that spread across the United States. According to Juliana Spahr’s analysis of the poem, “Claude McKay’s If We Must Die is the poem of this moment, one that captured the zeitgeist as if McKay were a prophet, and not a mere writer.”11

Along with politics, the magazine’s visual material included a variety of illustrations and cartoons contributed by artists such as Cornelia Barns, William Gropper, and Art Young.

Born in Philadelphia in 1888, Cornelia Barns was an American illustrator and suffragette. She began contributing illustrations to Eastman’s first magazine, The Masses, in 1914. Barns was one of a few women who played a significant part in the creation of The Masses. In 1917, Barns moved with her family to California with her husband and child. Committed to radical political and social change, Barns continued to provide art to The Liberator, New Masses, and Suffragist after moving to California.12

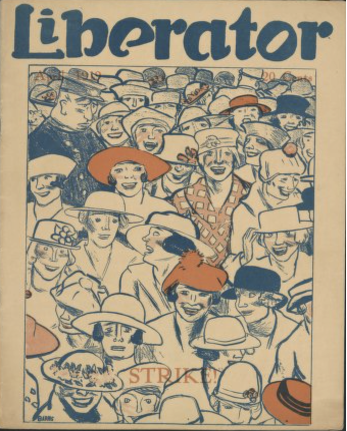

One of Barns’ most notable covers for The Liberator, Strike!, depicts women from the International Garment Workers Union who, in 1919, went on strike for a 44-hour work-week in New York.13 Inside the magazine one could learn more: “Our Cover design, drawn by Cornelia Barns, will carry to readers all over the country something of the spirit with which Local 25 of the International Garment Workers is conducting its strike for the 44 hour-week in New York. Eighty-five percent of the strikers are girls. Of the 35,000 who went out on January 21st, 23,000 have already won their terms and gone back to work. The rest are sticking it out magnificently.”14

Contributions from famous American cartoonists Art Young and William Gropper cemented The Liberator’s status as an influential socialist magazine within New York’s publishing scene. Art Young (b.1866-d.1943) was an American illustrator and activist in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. In 1884 he moved to Chicago and studied art and supported himself by drawing newspaper cartoons. In 1903 he moved to New York, and worked as an illustrator for The Masses. After the magazine’s suppression by the U.S. government, Young worked with the Eastmans to produce artwork for The Liberator until the magazine was merged with other left-wing publications to form Workers Monthly in 1924.15

William Gropper was another illustrator who contributed his art to The Liberator. The son of Jewish immigrants, Gropper took art courses as a teenager at an experimental socialist school. After winning awards for his drawings, Gropper took a job with the New York Tribune. His supervisors at the tribune fired him when they discovered his left-wing political connections.16

By 1922, The Liberator achieved a circulation of 60,000 readers, but Max Eastman desired to shift focus towards book writing and left for the Soviet Union.17 When finances became an issue later that year, the Communist Party of America (CPA) moved in for a friendly takeover. The political party worked with Eastman, Dell, and other writers for the transition. By fall 1922, the magazine became an official organ of the CPA, and political content returned to the foreground.18

In 1924 The Liberator was merged with other magazines to form a new publication, Workers Monthly. The magazine would change names again to The Communist in 1927 until settling on the title Political Affairs in 1946.19

To learn more about The Liberator, visit the Special Collections and Archives exhibit, Race, Politics, and Women’s Rights: Visions of a New United States, curated by Nick Campigli, on the library’s main level across from the reference desk. Or, email archives@reed.edu to schedule an appointment with Reed Special Collections and Archives.

To learn more about The Liberator’s contributors, see the book Crystal Eastman: A Revolutionary Life, or view our catalog of Claude McKay’s literature.

- Daniel G Donalson, The Espionage and Sedition Acts of World War I Using Wartime Loyalty Laws for Revenge and Profit (El Paso: LFB Scholarly Pub., 2012), https://site.ebrary.com/id/10610281, 2-3.

- “Max Forrester Eastman (1883-1969) | American Experience | PBS,” accessed October 13, 2021, https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/goldman-max-forrester-eastman-1883-1969/.

- “Crystal Eastman,” American Civil Liberties Union, accessed October 28, 2021, https://www.aclu.org/other/crystal-eastman.

- “Crystal Eastman | American Lawyer, Writer, Activist,” Encyclopedia Britannica, accessed October 13, 2021, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Crystal-Eastman.

- “Max Forrester Eastman (1883-1969) | American Experience | PBS.”

- Poetry Foundation, “Claude McKay,” text/html, Poetry Foundation, October 13, 2021, https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/claude-mckay.

- Ibid.

- “Claude M’Kay, African Poet. Made Co-Editor” The Chicago Defender, accessed October 13, 2021, https://www.proquest.com/docview/491882707?accountid=13475&forcedol=true.

- “The Liberator, July 1919,” The Liberator, accessed October 13, 2021, http://dlib.nyu.edu/liberator/books/lib000020/, 21.

- “‘Our Precious Blood May Not Be Shed’ | Claude McKay,” Lapham’s Quarterly, accessed October 14, 2021, https://www.laphamsquarterly.org/roundtable/our-precious-blood-may-not-be-shed.

- Juliana Spahr, “Hearing the Pandemic in Claude McKay’s ‘If We Must Die,’” PMLA 136, no. 2 (March 2021): 254–57, https://doi.org/10.1632/S0030812921000158.

- “Barns, Cornelia Baxter (1888–1941) | Encyclopedia.Com,” accessed October 13, 2021, https://www.encyclopedia.com/women/encyclopedias-almanacs-transcripts-and-maps/barns-cornelia-baxter-1888-1941.

- “GARMENT WORKERS ORDERED TO STRIKE; Union Calls Upon 35,000 Members to Quit Their Employment At 10 o’Clock This Morning. APPEAL FOR GOOD ORDER Right to Discharge at Issue–Demands Include 44-Hour Weekend Advance in Wages.,” accessed October 15, 2021, http://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1919/01/21/97060727.html?pageNumber=22.

- “The Liberator, April 1919,” The Liberator, accessed October 13, 2021, http://dlib.nyu.edu/liberator/books/lib000016/, 2.

- “Art Young,” accessed October 14, 2021, https://academic.eb.com/?target=%2Flevels%2Fcollegiate%2Farticle%2FArt-Young%2F78052.

- “William Gropper | Smithsonian American Art Museum,” accessed October 14, 2021, https://americanart.si.edu/artist/william-gropper-1957.

- Paul Buhle, Marxism in the United States: Remapping the History of the American Left (London: Verso, 1987), 172.

- “The Liberator.”

- Ibid.