In a recent email to the campus community, President Audrey Bilger and Chairman of the Board of Trustees Roger Perlmutter declared that Reed would “prohibit any new investments in public funds or private partnerships that are focused on the oil, gas, and coal industries, including infrastructure and field services… [and] phase out all such existing investments in private partnerships in accordance with the funds’ typical life cycles.”

Bilger and Perlmutter acknowledged the efforts of student organizations like Greenboard and Fossil Free Reed in the Board’s decision to divest—but did you know that the history of student organizing for divestment goes as far back as the 1980s? The first big push for selective investment at Reed was driven by increasing concern about the South African apartheid state.

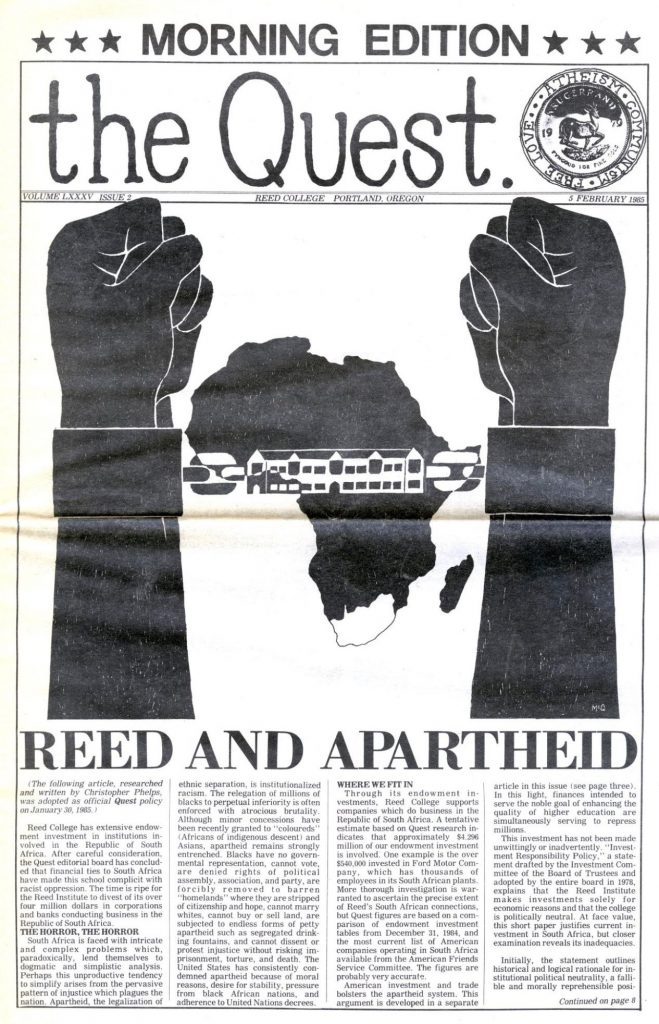

February 1985

The Reed College Quest published a special issue on apartheid, in which the editorial board took an official stance in favor of full divestment of college funds from companies doing business in South Africa. According to the Quest’s estimate, approximately $4.296 million of Reed’s endowment was invested in corporations with ties to the apartheid regime. The Quest editors argued that these investments made the college complicit in the exploitation of Black South Africans. In the following weeks, Quest editor Christopher Phelps and several other students organized the South African Concerns Committee (SACC), and started devising strategies to push the college’s administration toward divestment.

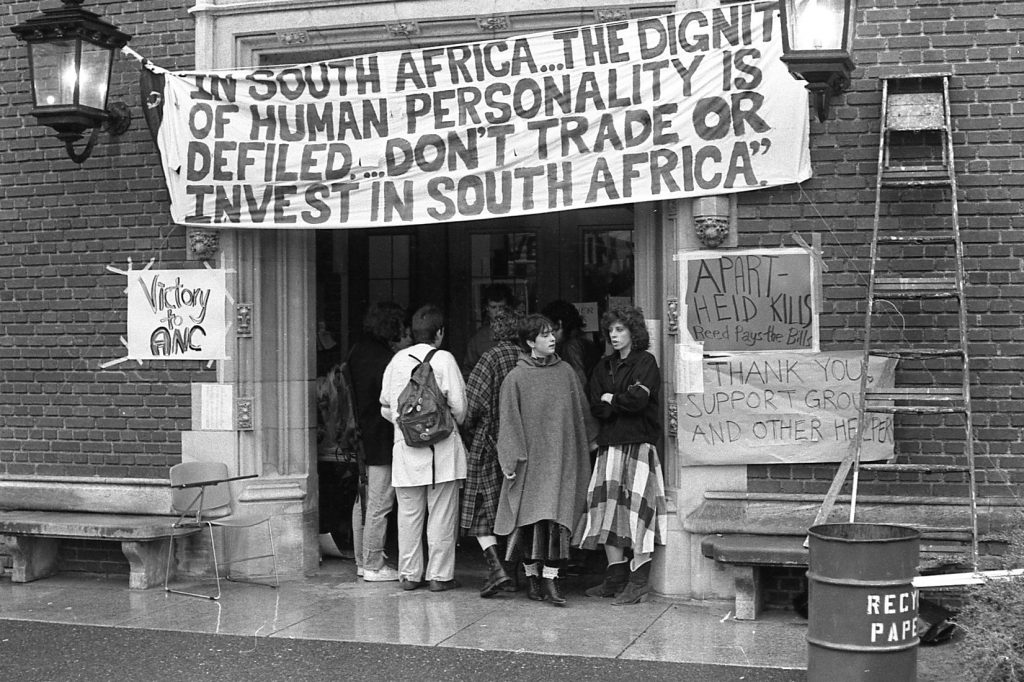

October 1985

SACC held its first mass demonstration, a non-disruptive protest in Eliot Hall. Not long after, SACC presented a petition to the Trustees that demonstrated over 50% of the college community favored full divestment. During the Trustees’ October meeting, the board chose to defer their decision to January 1986. In response, twenty-five students, unsupported by SACC, occupied Bragdon’s office in protest. Their attempts at negotiation with Dean of Students Susan Crimm were unsuccessful, and occupiers left the office after fifty-two hours.

January 1986

Bragdon delivered the college’s official statement on divestment: Reed would maintain its current investment portfolio, to the extent that it followed the Sullivan Principles**. In response, approximately one hundred students immediately took control of Eliot Hall, blocked all access to non-students, and demanded that the Trustees vote in support of full divestment and create more democratic financial decision-making structures. The use of barricades and unarmed guards at Eliot Hall’s entrances made the demonstration far more controversial than any prior SACC or divestment-related protests.

February 1986

The occupation of Eliot ended when occupiers reached an agreement with Bragdon and Crimm to establish a joint student-Trustee committee to deliberate on divestment and other issues of importance to the student body. Three other students levied an honor case against the occupiers, and argued that they had caused harm to the community by disrupting access to classrooms, the financial aid office, and other important spaces in Eliot. The Judicial Board decided that the occupiers were in violation of the honor principle.

Late 1980s

SACC renamed itself Reed Out of Africa and continued to push for full divestment, but was unsuccessful. Several students occupied the development office in Eliot Hall, but found that the administration was far less willing to attempt negotiation with them than before and received suspensions. Following Bragdon’s departure from the college in 1988, the issue died down.

Interested in learning more about the history of divestment efforts at Reed? Email us at archives@reed.edu, or visit our website!

* Divestment refers to the selective selling-off of business interests and investments, in compliance with set ethical demands. Apartheid divestment campaigns ranged from calls for divestment from companies that directly profited from the exploitation of Black South Africans (known as “partial divestment”), to companies that did any business in South Africa whatsoever (“full divestment”). While divestment has limited efficacy when it comes to placing financial pressure on companies and institutions, its modern proponents argue that it creates a moral stigma around unethical industries and labor practices.

** The Sullivan Principles were first published in 1977 by Reverend Leon H. Sullivan. They urged global “corporate social responsibility” through a set of seven principles intended to promote equal-opportunity employment practices. Over time Rev. Sullivan became increasingly disillusioned by their ability to effect social change, and by October 1985, he issued an ultimatum in an interview with New Yorker Magazine: “If apartheid is not abolished in actuality [within the next two years], all foreign corporations should leave [South Africa]. This should be followed by a total ban on all imports and exports.”

Works Cited

- Byshenk, Greg, Lynn Decker, and Michael Ames Conner. “Recent Topical History in Several Parts.” Reed College Student Handbook, August 7 1989.

- Kahn, E.J. “Sullivan Redux.” New Yorker Magazine, October 7 1985.

- Phelps, Christopher. “Reed and Apartheid.” The Reed College Quest, February 5 1985.

- Sullivan, Leon H. 1984. “The Global Sullivan Principles.” University of Minnesota Human Rights Library. http://hrlibrary.umn.edu/links/sullivanprinciples.html