Graffiti at Reed has been a contentious debate for the past four decades amongst both students and faculty. Some have viewed it as a valuable expression of free speech and student autonomy. Others have considered its presence a nuisance, one that degrades the college’s quality and reputation. Most of Reed’s graffiti has taken on a political bent, though at times it has purely been comical. From the 1980s till now the Reed College Quest has been the primary arbiter between those in support and those against graffiti.

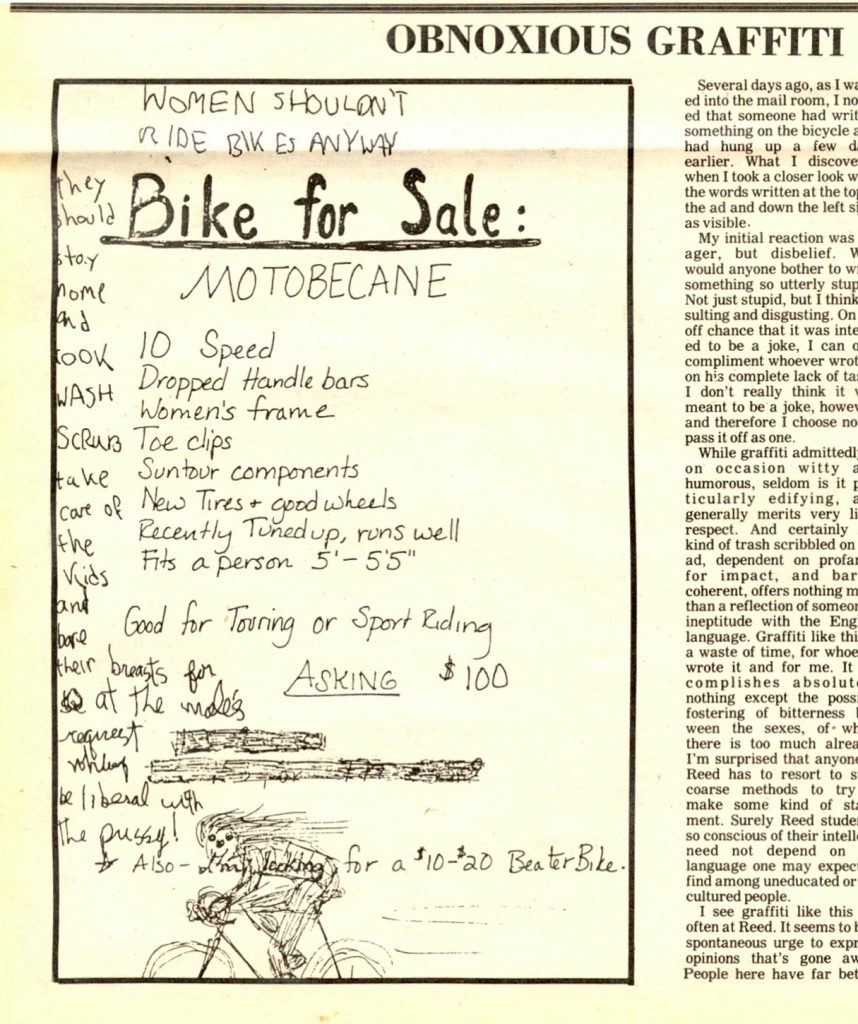

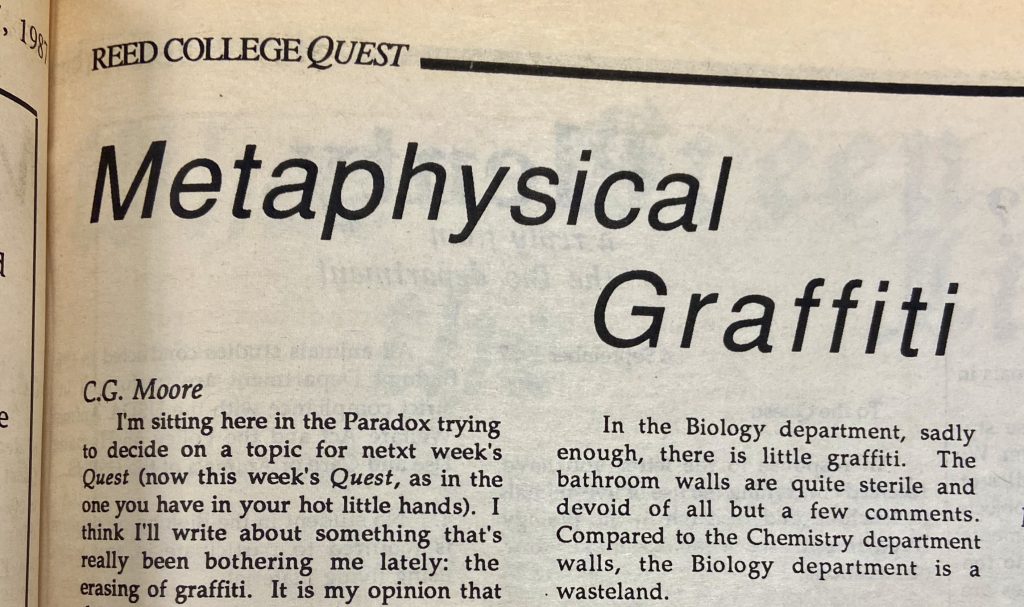

The debates surrounding graffiti in the 1980s were varied, with one article from November 14, 1984, decrying its existence due to its obscene nature. While the author acknowledges that graffiti on campus can be humorous, she critiques its occasional breach into problematic territory. On one such occasion, a student wrote on a bicycle ad that “Women shouldn’t ride bikes anyway.” We can all agree this is a poor use of ink, especially in an era when women’s rights were increasingly threatened. This was the 80s, when Ronald Reagan and the nascent Evangelical right were becoming increasingly powerful, and along with them came attacks on women’s reproductive rights. In 1987, another article, “Metaphysical Graffiti”, praised graffiti’s prevalence. Written in response to the erasure of graffiti by other students and campus services, the author argues that graffiti at Reed is unique when compared to “regular outside of Reed graffiti” insofar as it is creative, witty, and intellectual. Hence, “graffiti at Reed [should not be] thought of as defacing property so much as an anonymous forum for the expression of a diverse number of views”.

The article then discusses how different departments at Reed have their own brand of graffiti, like the Chemistry department’s graffiti which featured a chemical formula to make “Five-Pronged Werewolf Slayer.” Instead of erasing graffiti, the author argues it should be preserved and designated to particular spaces.

The 1990s brought about an era in which students were much less keen on graffiti’s ubiquity. This is, in part, due to dramatic increases in graffiti and general vandalism which occurred at the school during the era. The debate hit its peak in the late 1990s, with 1997 featuring almost monthly articles on graffiti’s prevalence. In February of that year, one article claimed that “graffiti as a means of social expression is tantamount to ethical cowardice insofar as the accountable party does not take responsibility for his/her viewpoints”. This was in response to the defacing of the new commons, which had recently been renovated. Another article published the same year, “Are We Gettin More Destructive?”, presented various arguments for why Reedies are “more destructive” than they once were, and argued that graffiti is the most obvious example of this increase in destructive habits.

Another hypothesis for the rise in graffiti was the closure of Commons’ lower level, a space traditionally used for student activities, which had the dual purpose of serving as a “natural outlet” for destructiveness on campus. Additionally, the lower level of commons was apparently used as a “sexual clearinghouse for the campus,” and because of its closure, students “have taken their excess sexual tension and channeled it into destroying the campus”. Another theory for the rise in graffiti is an increased number of students who are “volatile drunks and addicts [who] roam the campus,” who in their inebriated states wreak havoc on Reed’s infrastructure. While these are all compelling theories, the prevalence of graffiti certainly has not abated and continues to this day.

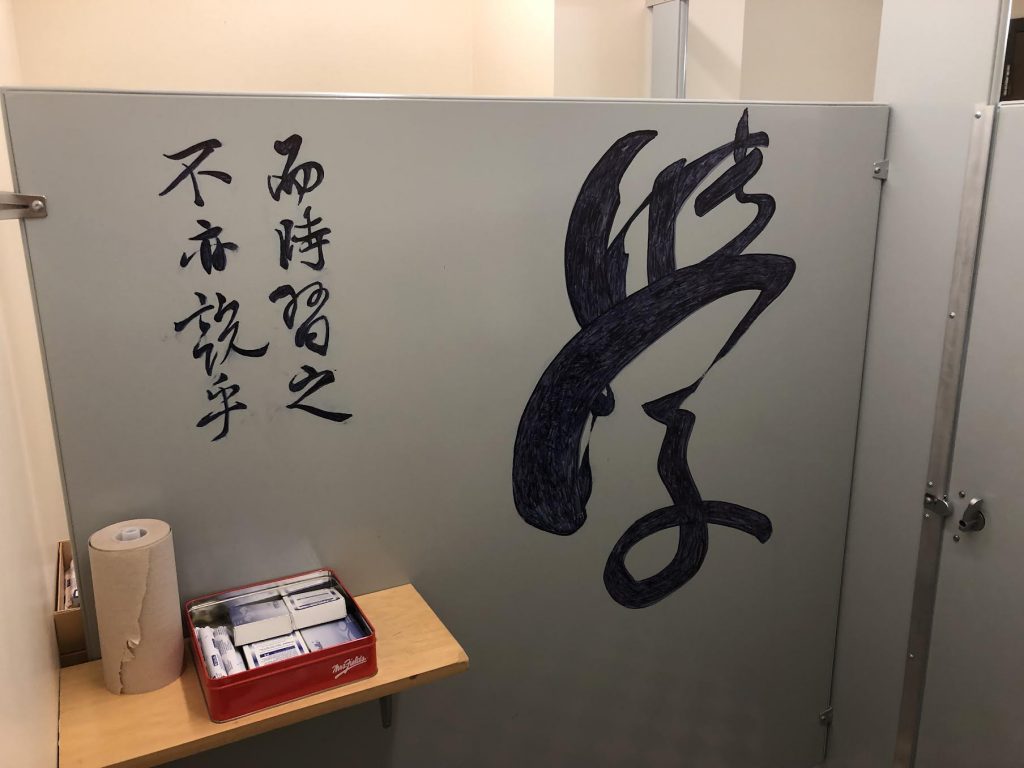

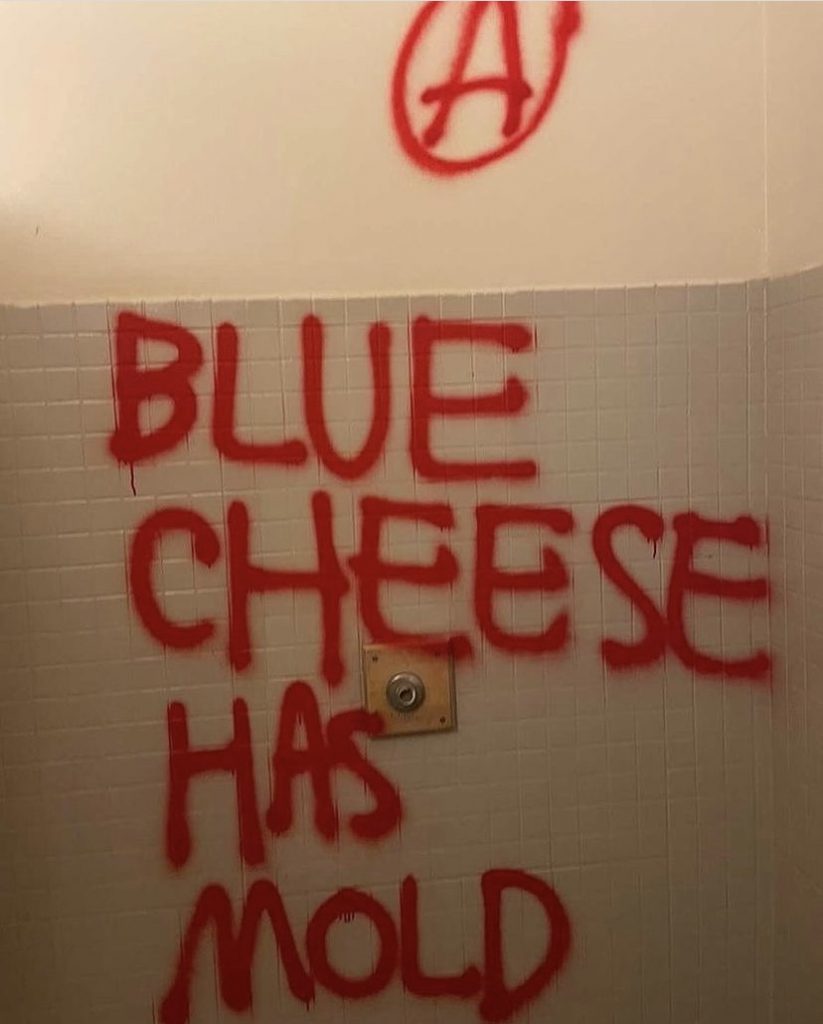

Graffiti at Reed in the twenty-first century has remained a staple of the SU and in campus bathroom stalls, and the occasional monumental design can be found on the side of buildings. To this day, both graffiti’s presence and its erasure by campus services is still being debated, with 2020 being a particularly controversial year due to the country’s political environment. While most graffiti has been tame, there have certainly been instances where graffiti has been used in harmful ways. If you want to see more pictures check out our digital collections, or visit special collections and archives, or email us at archives@reed.edu.