I can actually tell how your country accessed tea leaves just by the way you say it. It’s not a magic trick or an elaborate mental gymnastics. The history of tea is broad, deep and a topic of heated debates. Ranging in various flavors from white herbal to decaffeinated earl gray, tea became a stable aspect in cultures across the world. And for such a widespread word and cultural phenomena one would expect that each language would develop a unique term to describe this healing liquid, right?

Not quite. Etymology of tea extends to just 2 derivatives: “tea-derived” and “cha-derived”. This etymology doesn’t depend on what linguistically family you speak — both Russian and Kazakh use the “chai” variation despite belonging to a Slavic and Turkic groups respectively. Similarly, both Armenian and Sudanese share a common “tea-“ derivation even though Armenian belongs to a unique branch of Indo-European family while Sundanese is an Austronesian language — thousands of miles apart.

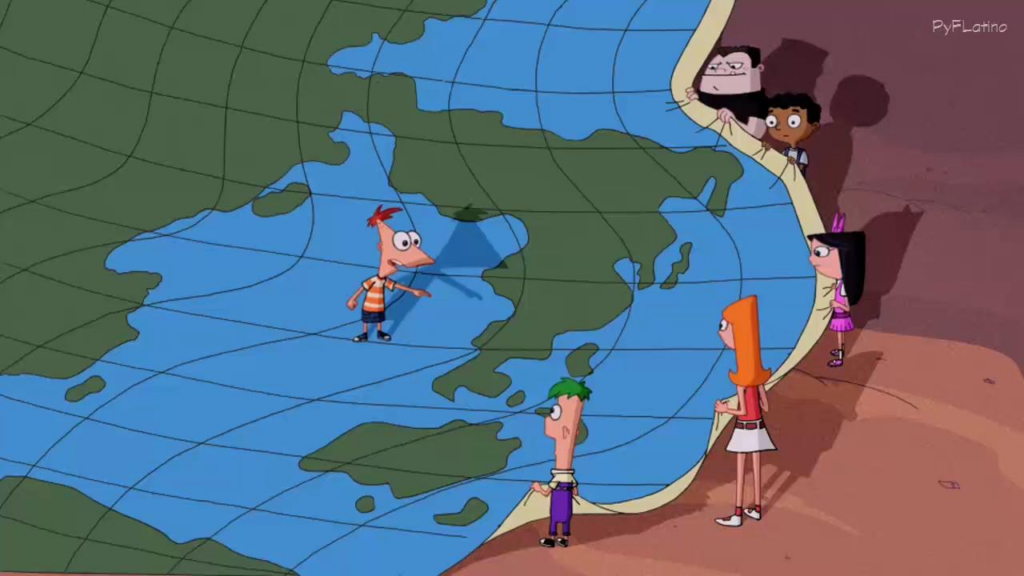

The secret lies in the means of transportation, and more specifically, the space by which tea has conquered the world.

The term cha (茶) is “Sinitic,” meaning it is common to many varieties of Chinese. But most importantly, its roots are in the non-coastal Eastern part of China and spread the world through the ocean: first reaching Central Asia until it reached Persia and Eastern Europe.

Meanwhile, the “te” form used in coastal-Chinese (still East!) languages spread to Europe via the Dutch, who became the primary traders of tea between Europe and Asia in the 17th century. The Dutch ports mainly resided in Fujian and Taiwan where the local population used the “te” variations allowing this specific form to be spread via ocean.

To put it simply, if you say “chai” then you got your drink through land trade, and if you say “chai” you can thank the ports and ocean.

Of course, there is always room for a few exceptions. For instance, Polish uses the word “herbata” whose phonetics closely resemble that of English “herbs”. Thai language also stands out — instead of the internationally acclaimed “tea” or “chai”, Thai speakers use the term “miang” translated as “fermented tea leaves”.

Makes you think twice about ordering “chai tea” next time!