Graphic novels are a huge form of popular media in France. Most French public libraries dedicate a large section to the bande dessinée alongside more typical forms of literature. French graphic novels have a flavor that is somehow both romantic and sordid, and a pace that runs much slower than a comparable American comic strip (the French are less concerned whether the story has a hero, follows an arc, or moves towards any resolution). They are typically very funny. Lucky for us, the Reed College library has several shelves of French bandes dessinées! For this blog, I read and reviewed four of them.

Most of the stories I read for this blog are in the realm of the fantastic, and I recommend going through slowly to absorb both images and the text. Sit down with a notebook and a dictionary, and plenty of time to take in both art and storytelling. These books are accessible to intermediate or advanced readers.

Finally, these graphic novels are a great source of new vocabulary since they include plenty of colloquialisms. A set of flashcards on Quizlet is linked below with my favorite words and phrases from the bandes dessinées I read.

https://quizlet.com/237885378/french-phrases-of-interest-flash-cards/

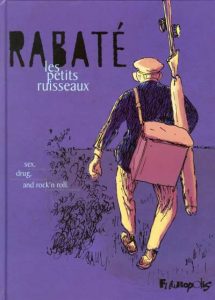

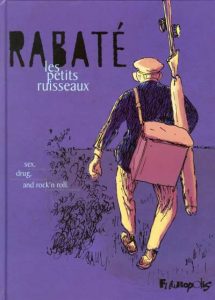

Les petits ruisseaux, Pascal Rabaté. 2006.

Call no. PN6747.R33 P48 2006

This story follows an old man named Emile who no longer finds much meaning in his old age. One day while out fishing, his best friend tells Emile to stop pitying himself and take full advantage of life while he can. Emile’s quiet life of solitude ends abruptly when he starts to take this advice. Do we assume that life and lust belong to the young? The tricks up his sleeve are predictable, but Emile’s character is compelling and it’s funny to see his sleazy side let loose. This bande dessinée won the Grand Prix de la Critique in 2007 from L’Association des Critiques et journalistes de Bande Dessinée (ACBD). It was made into a film in 2010.

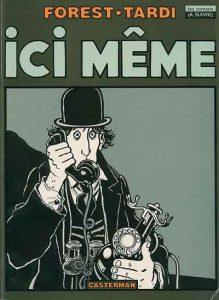

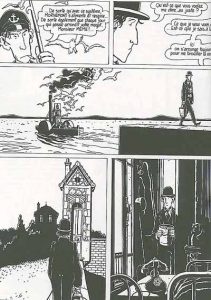

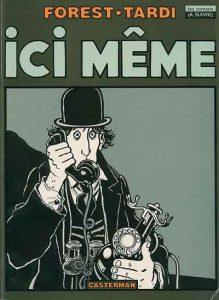

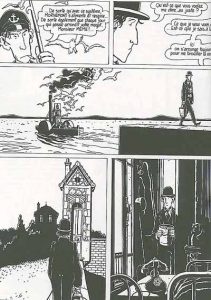

Ici Même, Jean-Claude Forest et Jacques Tardi. 1979.

Call no. PN6747.F687 I35 2006

This is a strange fairy tale about a man who lives atop the walls surrounding a neighborhood. He is not allowed to descend or set foot on the land below. Arthur Même, as the man is called, walks a fine line between dignity and mania, satire and hyperbole, as he gatekeeps for the wealthy socialites beneath the walls. A boatman comes once a day to deliver mail, cheese and wine. These are Arthur’s only interactions. The plot is full of tropes (spies, an ancient inheritance, war between the families, and a love affair) but intriguing nonetheless for its oddity. The novel is in black and white.

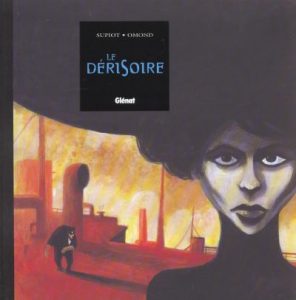

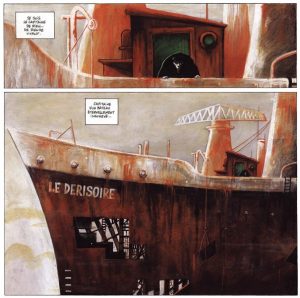

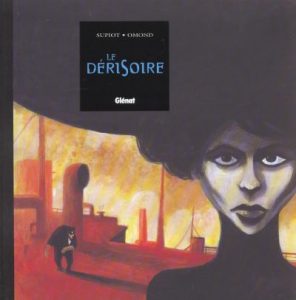

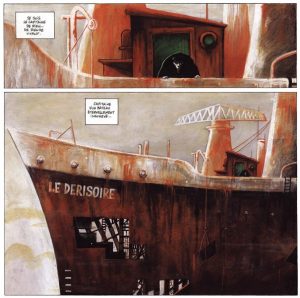

Le Dérisoire, Olivier Supiot et Eric Omond. 2002.

Call no. PN6747.S85 D4 2002

Le Dérisoire is a mix between Moby Dick and Alice in Wonderland. It features a solitary captain on a derelict ship in the ocean, going nowhere, in despair about his situation and his inability to fix it. His crew are all skeletons, having died some time ago, yet somehow remaining on board the ship. It seems that nothing ever leaves the ship and the ship itself never leaves. The furnace at the heart of the ship has gone out, leaving only cold empty steel, but still it floats. And which of the characters are living? Into this drifting tapestry comes a phantom woman, Constance, who brings color and life onto the ship. Is she real? Is the ship? Is anyone? The graphic novel has a dreamy watercolor-like style and is beautiful enough that it doesn’t matter that the plot doesn’t make sense.

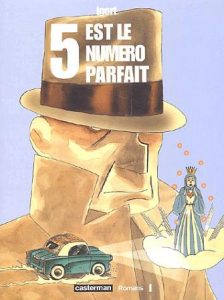

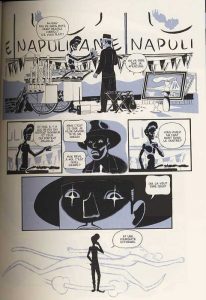

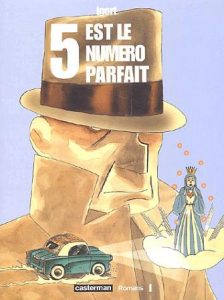

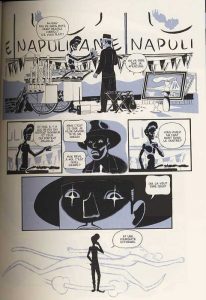

5 est le numéro parfait: 1994-2002, Igort, translated from Italian by Lidia Licari. 2002.

Call no. PN6767.I36 A6314 2002

This graphic novel was originally a three-part series that was later collected into one large volume. It follows a family in Naples embroiled in classic 50s-era mob drama. Think The Godfather–there’s shootouts in the woods, religious symbology, intimate family scenes, rivalries and backstabbing. The book moves quickly, lots of people get shot, and there is only one woman, the damsel in distress. This is a true Italian action comic, with a minimalist art style in grayscale and simple block colors. The author, who writes under the name Igort, has been at the center of the Italian comic scene for decades and published many other graphic novels. 5 est le numéro parfait is his most famous.

Copyright: All images taken from www.bedetheque.com/

“Les petits ruisseaux,” Pascal Rabaté. Futuropolis. 2006. https://www.bdgest.com/chronique-1530-BD-Petits-ruisseaux-Les-petits-ruisseaux.html?_ga=2.50200686.916534693.1512955637-12593617.1508988380

“Ici Même,” Jean-Claude Forest et Jacques Tardi. Casterman. 1979. https://www.bedetheque.com/serie-1684-BD-Ici-Meme.html

“Le Dérisoire” Olivier Supiot. Glénat. 2002. https://www.bedetheque.com/serie-6173-BD-Derisoire.html

“5 est le numéro parfait,” Igort. Casterman. 2002. https://www.bedetheque.com/serie-5200-BD-5-est-le-numero-parfait.html