Category: Announcements

-

Checking out books over summer

If you would like to checkout books over the summer or extend the ones you have, please stop by the circulation desk. A library staff member will update your account accordingly.

-

End of semester library hours

Library hours through Monday, 5/16 as follows – Hauser Regular hours through Wed. 5/11Closed Thur. at midnight 5/12Closed Fri. 5p, 5/13Closed Sat/Sun, 5/14-5/15Open Commencement day Mon. 5/16, 8:30-11a, 2-5p. IMC Regular hours through Fri. 5/13 PARC Regular hours through Sat. 5/7Open 10a-5p, Sun. 5/7 – Thur. 5/12Closed Fri. 5/13 PLEASE NOTE: THE LIBRARY WILL BE…

-

Now hiring – Acquisitions Specialist

Reed College seeks an innovative and service-oriented Acquisitions Specialist to procure current and out-of-print materials, in all formats and languages. In this position, you will collaborate with a team of library specialists and subject librarians to support students and faculty engaged in research, inquiry, and coursework throughout the curriculum. Reed College offers an exceptional benefits…

-

Reference Assistant Spotlight: Yoela

Name: Yoela (they/them)Year: SeniorMajor: Religion Favorite library resource: The stacks! Specifically rolling through the stacks to find book after book Favorite place to study in the library: North stacks basement and miscellaneous second floor couches Reason you wanted to be a reference assistant: I love the Reed library! A Reed librarian taught me how to…

-

Tales from the Archive: The Big Debate: Graffiti at Reed, 1980-2021

Graffiti at Reed has been a contentious debate for the past four decades amongst both students and faculty. Some have viewed it as a valuable expression of free speech and student autonomy. Others have considered its presence a nuisance, one that degrades the college’s quality and reputation. Most of Reed’s graffiti has taken on a…

-

Reference Assistant Spotlight: Nina

Name: Nina (she/her)Year: JuniorMajor: Sociology Favorite library resource: The many esoteric databases and the zine library! Favorite place to study in the library: The cubicle desks by the L2 Center Stacks. Reason you wanted to be a reference assistant: I wanted to help make the library feel more accessible to students; the many resources are…

-

Reference Assistant Spotlight: Ella

Name: Ella (she/her) Year: 2022 Major: Psychology Favorite library resource: Online journal articles Favorite place to study in the library: Pollock Room Reason you wanted to be a reference assistant: I wanted to learn more about library resources and help people access them. Hardest thing about research: When articles don’t have the keywords you expect, which…

-

Book exhibit: Counternarratives: Critical Race Theory in Context

Counternarratives: Critical Race Theory in Context is a new book display that seeks to expand, contextualize, and nuance the conversations about theories of race and racialization in academia and contemporary debate. Unlike what liberal and conservative media would like you to believe, Critical Race Theory is NOT a catch-all term for anything written by or…

-

Tales from the Archive: Divestment and the Occupation of Eliot Hall

In a recent email to the campus community, President Audrey Bilger and Chairman of the Board of Trustees Roger Perlmutter declared that Reed would “prohibit any new investments in public funds or private partnerships that are focused on the oil, gas, and coal industries, including infrastructure and field services… [and] phase out all such existing…

-

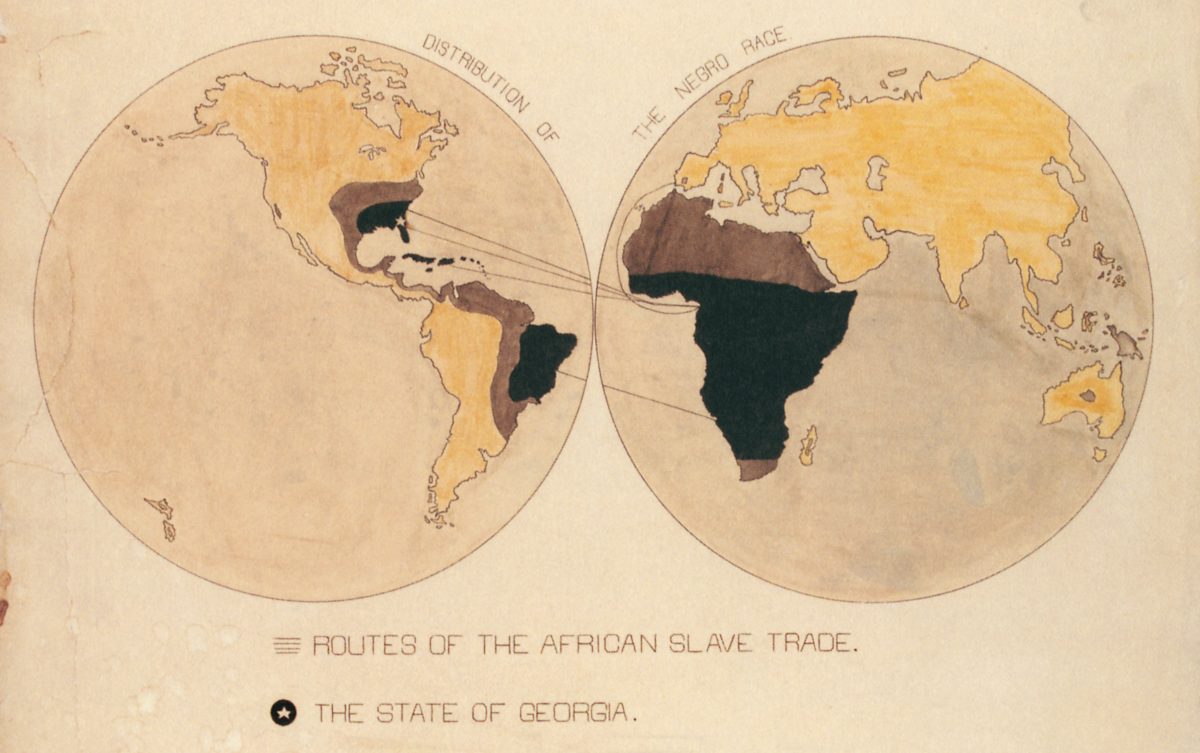

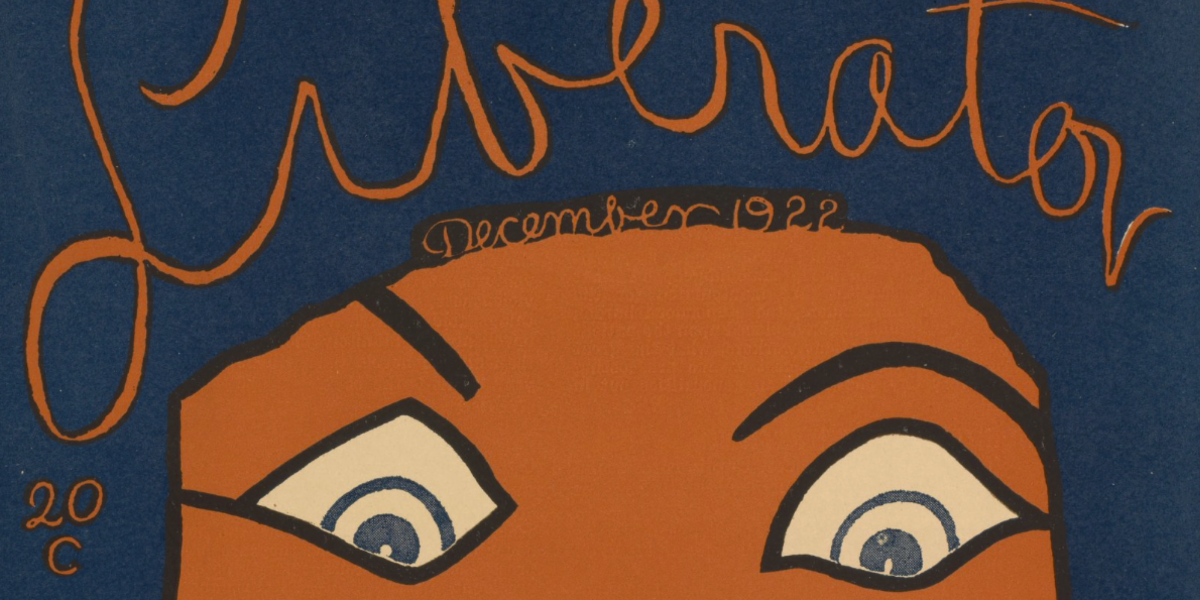

Exhibit: Race, Politics, and Women’s Rights: Visions of a New United States

Many have already heard of The Liberator, the 19th-century abolitionist newspaper created by William Lloyd Garrison. However, a new magazine under the same name emerged in the twentieth century. First published in the spring of 1918, the twentieth century Liberator continued the fight for equality: it focused on worker’s rights, women’s rights, and promoted socialism…